State of Belief

Strong Women Speaking Truth to Power: Kristin Du Mez and Mary J. Novak

Mary J. Novak and Kristin Du Mez are two incredible women whose work at the intersection of activism and faith is driving critical change in our society. This week, they join host Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush on The State of Belief, Interfaith Alliance's weekly radio program and podcast, to explore how faith can be used as a tool for tremendous social progress, or for abuse – and how people can work together to help foster inclusive communities and challenge the forces of oppression.

Kristin's new film, For Our Daughters, explores the troubling culture of submission and sexual abuse within the evangelical church, and its connection to the Christian nationalist agenda aimed at undermining women's rights in the upcoming 2024 election.

“I thought it was really important to put their stories, in all of their power, in front of the country. In front of Christian women in particular, in front of Christians, and just hear them and grapple with: how could this be allowed to happen? How could, even after these wrongs were exposed…How could this persist? And then, what are we doing as Christians, as church members, and as voters to perpetuate these systems that foster abuse?”

Kristin Kobes Du Mez, New York Times bestselling author and Professor of History and Gender Studies at Calvin University. She holds a PhD from the University of Notre Dame and her research focuses on the intersection of gender, religion, and politics. She has contributed to The New York Times, The Washington Post, and NBC News and has been featured on NPR, CBS, and the BBC. Her latest works include her book, Jesus and John Wayne and groundbreaking documentary, For Our Daughters: Stories of Abuse, Betrayal, and Resistance in the Evangelical Church.

“People of all backgrounds and religious and cultural persuasions are working together to help build the common good through policy and politics…because we can all come together. And when we collaborate, we have the power to decide the future we will inhabit.”

Mary J. Novak, Executive Director of NETWORK Lobby for Catholic Social Justice, the first lay leader and the sixth woman to hold this role. With a background in organizing, activism, law, education, chaplaincy, and restorative justice, she introduced a shared leadership model to advance NETWORK's mission. Under her guidance, the organization is building stronger partnerships for the common good and positioning itself for future growth in pursuing justice. NETWORK organizes the incredible Nuns on the Bus & Friends Tour, traveling across the country starting September 29th to directly advocate for and pursue social justice through the lens of Catholic social teaching.

Please share this episode with one person who would enjoy hearing this conversation, and thank you for listening!

Transcript

Paul Raushenbush:

Mary J. Novak serves as Executive Director of NETWORK Lobby for Catholic Social Justice. In April 2021, she became the sixth woman and the first lay leader to guide the organization, which was founded by Catholic Sisters over 50 years ago. Previously, Mary was at Georgetown University Law Center as a mission integrator and adjunct professor of law.

Mary's experience as an organizer, activist, trauma-informed lawyer, educator chaplain, and restorative justice practitioner informs her ability to integrate all aspects of NETWORK to advance the organization's mission, and has inspired her to initiate a shared leadership model for the first time in NETWORK's history. With the first in-person Nuns on the Bus tour in six years coming this fall, I am really happy to welcome Mary Novak to The State of Belief. Welcome, Mary.

Mary Novak:

Thank you, Paul. It's really good to be with you.

Paul Raushenbush:

Thank you. Oh my God. I have waited for this for six years! The Nuns on the Bus ride again. This is so exciting. We're going to go back and talk about what NETWORK lobby is and all about you, but I do want to start with the exciting headline that the Nuns on the Bus along with friends will ride again.

Can you say a little bit about what this means and where you're going and what you're hoping to accomplish?

Mary Novak:

Thank you, Paul. This is the question for me, today, as well. So starting September 30th, the Nuns on the Bus & Friends will embark on our Vote Our Future Tour. We will visit 20 cities in 11 states over three weeks.

The tour will begin with a kickoff in Philadelphia on September 30th, and conclude in San Francisco on October 18th. Along the way, bus riders will participate in town hall events, rallies, small group discussions, and press conferences, as well as site visits at local social service agencies and community organizations.

Paul Raushenbush:

This is so exciting. Congratulations. And that is an ambitious schedule. I'm sure it's kind of like the date is coming at you and you're like, okay, we're really going to do this.

Mary Novak:

I’m one of the few people who will actually be on the bus the whole time. So everybody else will be on for a particular leg. I get to do it the whole time. So I'm actually in training to be able to sustain that three-week tour.

Paul Raushenbush:

I assume you're driving the bus. Do I have that right?

Mary Novak:

No, we actually have a bus driver.

Paul Raushenbush:

Okay, good. I think that makes sense. Now, this is really interesting. What I've loved about NETWORK Lobby over the years is that you raise up issues in a way that is bipartisan. It's really about caring for the people and bringing out that Catholic social justice tradition, which is a huge part of the American tradition.

I can imagine when you're doing this Nuns on the Bus & Friends tour, you're going to sites that really bring out the question: what are we doing for one another? How does our body politic impact the way we actually love our neighbors? So, what are some of the examples of places that you're going with the Nuns on the Bus? What are some of the stops that will highlight that question, how do we love one another in ways that are tangible and life-changing?

Mary Novak:

Absolutely. Well, let me give a little bit more background, Paul. Through the past seven tours, Going back to 2012, Nuns on the Bus have advocated around moral budgets, tax justice, mending the gaps in our social safety net, and the simple fact that who we elect matters.

So this tour, we are advocating for Catholics and all people of goodwill to be multi-issue voters, because that is the only way to protect and preserve the freedoms that help individuals and communities to flourish in a vibrant, inclusive, multifaith, multiracial democracy. Pope Francis is really good on all of this, because he says, the only future worth building includes everyone, right?

Paul Raushenbush:

Wow. You've said a bunch of things there that we don't hear very much about, but we can actually count on the sisters and all the people around that tradition, Catholic social justice. What does it mean to have a moral budget? That's a really good question. Look to where the money is spent and you'll figure out where the priorities lie. I love this because it takes it out of the personalities of the politicians, and it actually grounds it in: well,what does it look like when the policies they represent are enacted, and what are the implications for the people? And also, this broader holistic understanding of the multiple issues at stake in an election like this, including democracy itself.

I'm just curious as someone who is a lawyer by training and has a deep commitment to the Catholic social justice tradition, how do you understand the state of play of our democracy in this moment?

Mary Novak:

It is absolutely fragile. Paul. I have been giving talks across the country for the last two years to primarily Catholic organizations talking about how international democracy experts all agree how fragile our democracy is. And that has been downgraded over the last 17 years, and we have all the indicators necessary for a civil war because of the polarization that is at play, that politics and bad actors play upon to divide us even more.

Paul Raushenbush:

Just to underscore what you're saying, we have been recategorized as a backsliding democracy. You know, we kind of think of ourselves as the shining beacon on the hill. What happened to that? But actually we are at risk. And to recognize the dangers that have been posed and some of the rhetoric that is being used, already, in this election is terrifying to me.

Mary Novak:

It is. I want to come back to something you just said, we do hold ourselves out as the oldest democracy in the world; but in fact, Paul, we did not really choose to be an inclusive democracy until 1965. Because our original democracy excluded Black folks and women and indigenous folks - we can go through the long list, right? And so we only started trying to be an inclusive, multiracial, multi-faith democracy in 1965 with the passing of the Voting Rights Act.

So really, international democracy experts put us on par with the second wave of post-colonial countries in our experiment of democracy. So it's actually not that we are backsliding so much as that we are at this pivotal moment in our evolution, which is actually much younger than we like to admit.

And yhat pivot is actually helpful for many people, because most people are in despair if they look at our democracy. But if you then say: but it's a rather new democracy, this is growing pains. This is what it takes to evolve. Then that switch of meaning-making is so helpful and inspiring to people.

Paul Raushenbush:

Right, instead of a backslide and, oh no, oh no, actually, this is growing pains into the future. And what does it look like to grow into the future? And what kind of work do we have to do now to actually make sure that future is realized for everyone?

And that I think, back to the Nuns on the Bus, because I can't let it go, that's our campaign, right?

Mary Novak:

Well, that’s actually our campaign. It’s Vote Our Future. And we're advocating for Catholics and all people of goodwill to be multi-issue voters.

When Pope Francis was talking about being multi-issue voters, that there are equally sacred other issues besides protection of the unborn, back then he was primarily in conversation with the issue of abortion, and then he expanded it out in this wonderful document called Rejoice and Be Glad in English.

This year I have talked to a lot of young voters who will have their own single issue that is starting to determine who they vote for. And it's Israel and Gaza. So for them, I'm also saying, can you pull back and become a multi-issue voter and look at all the issues at play, bring that into your prayerful discernment, because that is what the sisters have been inviting, and we continue to invite folks across the country to do for this election.

And it's really helpful to think about Israel and Gaza and abortion. And for some climate folks, they think climate's the only issue. So let's bring it all into the prayerful discernment.

Paul Raushenbush:

Yeah. Let's, go back a little bit to talk about the founding of NETWORK. How did it happen? It's just so interesting to me because some of the most awesome, radical mentors of mine - Sister Joan Chittister was a major influence on me, of course, Sister Simone Campbell - so many along the way have really helped me understand myself as a religious person, what it means to be a religious person, inspired me and so many of us.

But to organize is different than to be individual inspiration. You know, individual inspirations rather than an organized inspiration that will step out and say, actually, this is what we're standing for. Talk to us about the origin story.

Mary Novak:

So I know most Protestants are familiar with what happened in the Catholic Church in the early sixties, Vatican II. And I don't want to be reductionistic as I talk about that important multi-year process in our tradition, but it really moved the Church from being inwardly-facing to outwardly-facing. And called all people to holiness.

This was a moment when all people of God were called to own their baptism, and act out of that sacred blessing. So Catholic sisters, like all religious - men and women who were in orders of congregations - they had a specific directive coming out of Vatican II to go back to their own origin stories and get connected with their founding charism, and bring that forward to the 20th century.

Catholic sisters, being who they are, and given that they always take seriously what they are called to do, were the first ones out of the box, looking at their charisms, updating their ministries. They left their traditional ministries of healthcare, education, and pastoral work, and they became community organizers.

They started to do direct service work in their communities.Almost overnight, they said, ah, structural change has to happen because many of the people we're serving are not poor and on the fringes of our society because of any individual action of theirs. This is about a structural issue that can be fixed at the federal and state levels.

So they came together in Washington in 1971, 47 sisters. Many of them were organizers, but many of them were still in their traditional ministries. And they said, what can we do to affect structural change? Well, we can become a network of our sisters all over the country who are in the community. Bring that information to Washington and have a small organization in Washington that lobbies on Capitol Hill and lobbies the administration for structural change.

Paul Raushenbush:

That is an amazing story. It's such an aha moment for me: of course, Vatican II to NETWORK lobby, I hadn't made that connection, but that makes total sense. And also it's really interesting because this kind of move from you're very immediately engaged with the suffering of people - in education… It's not “suffering,” suffering is just as reductionist as well. The lives of people who are really challenged with all sorts of things not of their choosing, not of their making. They’re a structural obstacle.

There's the great parable that my great-grandfather, Walter Rauschenbusch, did this little sermon about, with, you know, we talk about caring for the man who was attacked on the road, and actually caring for them. But if it kept happening day, after day, after day, at some point, you're like, how can we stop that guy from getting attacked in the first place? That's what we're really talking about here. It's the good Samaritan story.

The good Samaritan story eventually moves to NETWORK Lobby saying we're going to stop this. I was at HuffPost doing the religion coverage in a moment where it was kind of amazing to watch the Catholic sisters in “conversation” – I’m going to use that nice word - with the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, who were like - and again, this is all me from the outside using words, so I'm not putting any words in anybody's mouth, but it seems like those ladies are getting a little uppity and mouthy. Maybe, maybe we should stop them from talking so much and doing so much. It seemed like there was, within the Catholic Church, there's always been a little bit of a tension about who gets to speak for the Church.

Is that a fair way to put it?

Mary Novak:

I think that there is absolutely that at play. And let me be clear, the Catholic bishops speak for the institutional Church. They speak for the Church. The distinction that Catholic sisters have always made is that Catholic sisters and us lay folks who continue their vision, we speak from the Church – and that all the voices are critical. And we are on the ground, walking with people in their lives, day to day. And so that's an important voice to be part of the conversation.

And at best, the institutional voice and the voice from the Church should be in dialogue or at least creative tension.

Paul Raushenbush:

I'm a Baptist, and you say, like, two Baptists, three opinions or four or five, you know what I mean? There's no reason to apply a standard that I don't represent myself in my own Protestant tradition to the Catholic Church. And even among the bishops, they don't always agree on things. But it was really inspirational to see how this idea of talking from the Church, I'd never heard that before, but that's a really beautiful way to speak. So many of the bishops have done amazing work and continue to do amazing work. So it's not an either-or.

Back to the Nuns on the Bus. Give me a couple stops that you're excited about. You're going to be on the bus – wow - for a month or so. What's a stop that makes you think, okay, I'm really looking forward to this town hall. I'm looking forward to showing up there with our cool bus - which by the way, people have to Google Nuns on the Bus 2024 ‘cause they have a cool bus. So what are a few stops along the way in whatever cities you want to mention?

Mary Novak:

Well, because I'm a west coaster, I grew up in California, I have to say the western leg really excites me tremendously. And I grew up in a multiracial multifaith microcosm: California is the second state in the union to be non-majority White for a very long time. So that is what our country is growing into. I'm looking forward to going home in many ways, but starting with Tucson, Arizona, where we will go after Chicago, meeting with folks there around immigration and all that affects Latino Catholics.

In that region, we're going up to Las Vegas, then over to Bakersfield to talk to farm workers in that regio,n as well. And this is going to inform our thinking about the election, but also about the priorities. In the next Congress, the 119th.

Paul Raushenbush:

And what I love is that it's not just big cities. I think we often are like, well, what next urban center should we go to? And that's just not the reality - especially for immigration, because a lot of immigration is most present in rural communities where people are coming and filling in and making factories and agriculture work because they're there to do it. And so it's so important that you all will be there. It means a lot to communities for someone to come to them to listen to them.

You're basically saying, you're important, with every stop that you make. You're indicating to a population that they matter. And I think that's incredibly valuable, especially given the mission of NETWORK and your own passion. It feels very important that you're showing up in places and shining a light and saying, I really see you.

Mary Novak:

Absolutely. And the story of immigrants in our country is being overshadowed by political rhetoric and, you know, immigration has become yet another political wedge issue - when in fact immigrants contribute so much to our country. The GDP contribution of immigrants is mind-blowing when you look it up, and immigrants do so much in these small communities in ways that most people have no idea about. So we want to raise up their stories along the way, because that is how we counter the really dangerous rhetoric around immigration that is happening in our country today.

Paul Raushenbush:

I have to name it Some of this stuff, like poisoning the bloodstream. That is a fascistic phrase. It's abhorrent on its face value. But then even if you ask a question, like what bloodstream are you talking about? It's absolutely outrageous.

I was just talking to a friend of mine who immigrated here, and I was like, I have this privilege that my ancestors came here when it was an open border. There was a time - people forget that. It was, oh, you got the boat. Welcome. It was pre-Ellis Island. And immigration is something that has been reduced even to the rhetoric of unhuman. Animals.

This is real right now. It's some of the most shocking rhetoric, and the fact that it hasn't just arrested all of us and caused us to be outraged. I'm sorry. I'm ranting. I get it. I'm ranting, but this is rantable stuff. Back to immigration. You talk about a multi racial, multi religious society. In some ways, our question is, if you actually see that and think it's a positive thing and it makes us stronger, more rich in the sense of the beauty of it and the possibility of it, or if you think that's just a terrible thing.

And I think that's almost where we are as a country.

Mary Novak:

And Paul, you're getting to another very important piece that when I share it around the democracy analysis that I've already provided you, it makes people go, oh, that's also going on. By 2040, the United States will no longer be majority White.

That demographic shift is also at play here, where you have a demographic shift where the dominants are losing power. International democracy experts say no other major democracy has gone through such a demographic shift and the loss of power of their dominance. So this is a scary moment for many people. And so we have to be generous in how we understand the loss that most people don't even recognize.

Paul Raushenbush:

Yeah. But if you start to get into it, a lot of what we're experiencing and the ginning up of fear, and it comes down to this fear. Mother Teresa said something I think about a lot. She said: Don't fear the poor. And it expands out to: Don't fear the other. Don't fear what is not you. I think that's a really important way to understand what it means to love your neighbor. You can't love and fear at the same time. I think this is really important.

I want to talk a little bit about your own background, because I'm really into cool folks who use a law degree in a really interesting way. You know, I come from a law family. So many members of my family were lawyers. How did it go? Give us a little bit about Mary Novak, and how you got from, I'm going to go to school, to, I'm the head of NETWORK Lobby, or sharing leadership with NETWORK Lobby. What was the trajectory there?

Mary Novak:

Well, it was actually a call and another call and another call. I come from a working class background. I don’t come from lawyers, I don’t come from doctors. Based on a tragic circumstance in my own family, I realized we didn't know anything about the law. We didn't know anything about systems. And so when my younger brother had what they called back then a nervous breakdown - it was late adolescent onset of mental illness, and he got system involved, right? We had no idea how to navigate the criminal legal system, the mental health system, the healthcare system. And I realized I needed to go learn all about that. So I went to school and I became a lawyer, and I did bring all of those skills and gifts to help my family in the flourishing of my younger brother in the midst of his mental illness.

But it kept leading me to say yes to future calls. I had left Roman Catholicism because my parents had practiced a pre-Vatican II Catholicism that did not resonate for me. Fast forward when my next door neighbor in Davis, California, when I got moved there to become a public policy lawyer, a beautiful gay man who invited me to go back to church. At a Catholic church.

And I said, Richard, I can't go in there if you can't go in there. And he said, I can go in there, and come with me. And I said, okay. And he said, they welcome me. They've moved me into leading some ministries. This is a place that I have studied Catholic social teaching. I've learned all about the Jesuits and their work all over the world.

And I came back and I fell in love, hook, line, and sinker in this Catholic church that had moved from being centered on itself to centered on the world. This was a post-Vatican II community that was inclusive and welcoming and engaged in the community. And it was all the same prayers, Paul. All the same rituals, but in a different location.

Paul Raushenbush:

Wow, I just have to take a moment to just to underline how amazing to have a gay man bring you back to church. A lot of times people from the LGBTQ community find something in religious communities that they really need and love. And then they were like, you know what? If, if I can go, you can go; we can do this together.

That’s a beautiful story that I don't hear a lot, but I do think that that does happen and I think it's really cool.

Mary Novak:

Yeah. And so just along the way, I fell in love with theology, because it was the meaning-making component of the law that was missing for me. And so I left my for-profit practice of law. I went to teach law at a Jesuit school. I started studying theology. And one thing leads to another in this sacred journey that we all live, Paul, you know that. You say yes to this and it leads to that. And the journey all came together at NETWORK when Simone stepped down.

She didn't retire - because Simone will never retire. But when Simone was ready to move on to the next stage of her life, people wrote me and said, I keep reading this job description and I think of you. And I said, okay, I'll pray about it. It was in the middle of COVID. I was a little busy at Georgetown Law, but eventually, the process led to me saying this.

Paul Raushenbush:

Sister Simone was a lawyer as well, I believe. And similarly connected the law with a theology that made sense. And I just think that that's really beautiful.

Mary Novak:

And we’re both from the west coast ,too.

Paul Raushenbush:

That's right. That's right. I have had a chance to interview her a couple times. Obviously very inspiring. Right now you're doing Nuns on the Bus, but of course, all of us are looking to, what is the future? This idea of ,what is the promise of 2025? We're doing a lot of reacting to Project 2025, but I think the religious leaders in the broader spiritual community, we can think of what is the promise going forward and how can that draw us and make us focus on specific issues, policy issues that we really need to put forward.

As you look forward, whoever wins this election, there's things that need to be addressed. And so what are you all looking at? I'm very eager to see ways that Interfaith Alliance can partner with NETWORK into the future.

Mary Novak:

That sounds great. I'm going to get to your policy particulars in a moment, but actually, our bus is the way into that answer. Since our last in-person tour in 2018, Pope Francis has said some things that have captured our imaginations. So in preparation for the Synod taking place in the Catholic Church in Rome, he's instructed all Catholics to, quote, “enlarge the space of their tent,” unquote, and to be more inclusive and welcoming.

So last year, he said that he wants us to build a Church that is for everyone. “Todos, todos, todos” in Spanish, right? And so we have taken that to heart in creating our bus tour and in thinking about 2025, which I'm going to get to in a second. And that's why on our bus this time, Paul, we have both Catholic sisters, lay people like myself, and our interfaith and secular partners actually on the bus tour.

So of the three legs of the tour, we have a total of 15 Catholic sisters and 15 non-sisters that reflect the kind of collaboration our organizations are already doing, but we want to do more deeply. So these partners include Debbie Weinstein from the Coalition on Human Needs, Anna Garcia Ashley from the Gamaliel Network, Reverend Dr. Starsky Wilson from the Children's Defense Fund, Rev. Adam Taylor from Sojourners, Reverend Dr. Leslie Copeland Tunes from the National Council of Churches - just to name a few of the partners who are actually on the bus with us.

Now, the witness that this collaboration creates is kind of the true sign of hope for us, no matter what happens with the election. That people of all backgrounds, all religious and cultural persuasions, are working together to help build the common good through policy and politics, which again, gets us to why we call it Vote Our Future - because we can all come together. And when we come together to collaborate, we have the power to decide the future that we will inhabit.

We had a press conference to announce the bus at the end of July, Paul, and Rev. Dr. Starsky Wilson, good friend, said something that has just stayed with me when thinking about 2025. He said, instead of Project 2025, how about Matthew 25? And so that, of course, goes back to our origins. It goes back to the universality of Catholic social teaching, which you mentioned at the beginning. Catholic social teaching resonates across religious traditions.

And so we're waiting to see how the composition of the Presidency and the two Houses of Congress come together. We are putting our agendas together. Now, we will continue to do human needs, all the human needs works that we have done in the past. Immigration is going to be significant if we actually get a composition of the House, the Senate, and the presidency that can do comprehensive immigration reform.

It is also a moment in time for climate. If we do not do the institutional work at the national level around climate, the existential threat that we keep talking about will come nearer and nearer.

Paul Raushenbush:

So Mary Novak, the last question I ask every guest is what gives you hope?

Mary Novak:

Paul, your invitation to me today gives me hope. When I wake up in the morning and realize that there are faith leaders and faith-based organizations across the religious traditions that work together for a common cause, that keeps me going every day. And so I'm so grateful to be here with you today.

I just described our Nuns on the Bus & Friends bus tour reflecting not just Catholic sisters, but Catholic sisters with our interfaith and secular partners who do this work together. There's never been a moment in time more important in my lifetime to come together to do this work in the face of our fragile democracy.

Because the hope that on the other side of this, we will continue to live into this multiracial, multi aith, vibrant democracy where everybody matters. That gives me great hope. That is our common vision that I know we all share.

Paul Raushenbush:

Well, consider me a friend of the Nuns on the Bus.

Mary J. Novak is executive director of the NETWORK Lobby for Catholic Social Justice. The 2024 Vote Our Future Nuns on the Bus & Friends Tour starts September 30th in Philadelphia, with stops including Pittsburgh, Detroit, Chicago, Phoenix, and San Francisco. All the information you need is at nunsonthebus.org.

Mary, thanks very much for being with us on The State of Belief and for all that you and all the sisters are doing in our country today.

Mary Novak:

Thank you, Paul, for this invitation. It's been such a delight and joy for me to spend this time with you.

Paul Raushenbush:

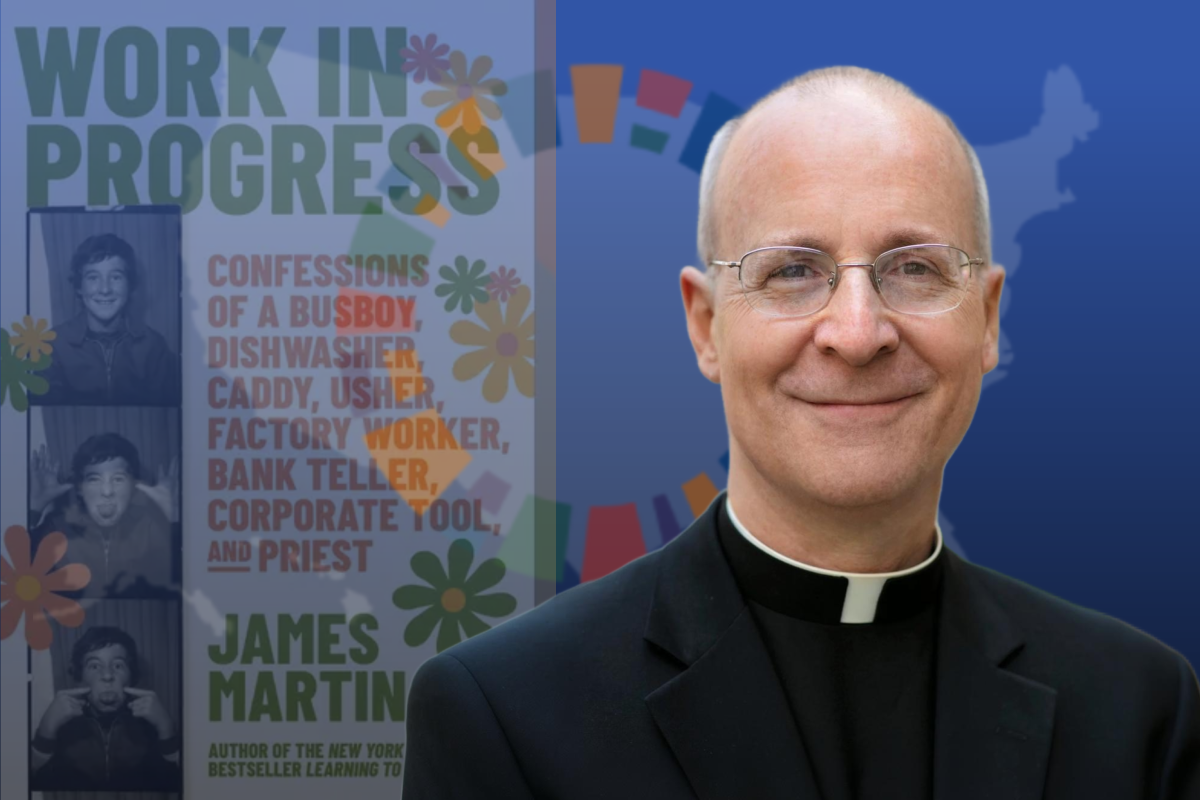

Dr. Kristin Du Mez is a historian of gender, faith and politics at Calvin University in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Her best-selling book is Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation. And her explosive documentary film, For Our Daughters, Stories of Abuse, Betrayal, and Resistance in the Evangelical Church, is available for streaming.

Dr. Du Mez, welcome to The State of Belief!

Kristin Du Mez:

Thank you so much for having me.

Paul Raushenbush:

I am so moved by your work. You have done something that needed to be done. First with your amazing book, Jesus and John Wayne, it altered the conversation. We all sat up and said, this is so important. And you really offered a vision for just how faith had been corrupted.

But also, I think you really shined a light on kind of this - it's a phrase that's being used a lot, but toxic masculinity, and how that really corrupts us. And it doesn't mean that - I hasten to say it - men are not bad, but there is a way that masculinity and a sense of unstoppable power and desire for power really has corrupted a faith tradition. So I start with gratitude for all that you're doing.

You come out of the evangelical tradition. This is not something you're, like, looking at with an interested little microscope saying, I wonder what these people are? You come out of this tradition.

Can you say a little bit about your background?

Kristin Du Mez:

Yeah, I would say I come from the edges of the evangelical world, in that I grew up in a small town in Iowa in an immigrant community, Dutch Reformed community. And I didn't go to an SBC church. I didn't go to Wheaton College or Moody Bible Institute, where the real evangelicals hang out - which I discovered when I went to grad school and studied evangelicalism with a lot of these hardcore evangelicals, and learned a lot. So I came from the edges of the evangelical world.

However, I will say I was immersed in popular evangelicalism as a kid growing up in the eighties and nineties. I listened to contemporary Christian music. I shopped at Christian bookstores. We only had one bookstore in my town. It was a Christian bookstore. And in some ways, I was immersed in this cultural evangelicalism even if I didn't identify personally as evangelical.

In fact, a lot of evangelicals don't identify primarily as an evangelical. They just see themselves as bible-believing Christians, and that's how evangelicalism works. It is a popular culture, and so it influences so many Americans, so many people around this globe, with their distinctive teachings - which are then actually packaged and sold as just plain old generic historic Christianity instead of what they actually are, which is often quite innovative. And in some cases I would say corrupting the biblical historical Christian faith.

Paul Raushenbush:

Yeah, it's very convenient when you say, we're just Christian. We are the Christians. Everyone else is divergent. It's a little bit of a trick.

I really want to get into your your great new documentary, which I - hold on to your hats, people. This is really important. But before we get there, talk about your impetus for writing Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation. Jow did you get there? And what are some of the most important messages that still remain as true as they were when this was published?

Kristin Du Mez:

Yeah. Oh, even so, it seems. I came across the topic of Christian masculinity, evangelical masculinity, in the early 2000s. It was actually my students at Calvin University that brought this to my attention.

I had been teaching a class in American history on Teddy Roosevelt, and I taught how he had embodied a new type of masculinity in the early 20th century, one that was tied to whiteness and imperialism and militarism. And after that lecture, a couple of guys came up to me and said, Professor Du Mez, there's this book that you have got to read. And that book was John Eldridge's Wild at Heart.

And I went down to Family Christian Bookstore, bought myself a copy for $19.95, and I opened it up, and there right in the opening was a quote from Teddy Roosevelt. And I went on to see how the entire vision of quote unquote “Christian masculinity” was one of militarism.

God is a warrior God, and men are made in his image. Every man has a battle to fight. So I thought, wow! Where did this come from and what is this doing? And at that point my focus was actually more on foreign policy. This was the early years of the Iraq war. And we could see how evangelicals, more than any other demographic, were pro-war, pro-torture, pro-aggressive foreign policy.

And knowing how cultures work and how cultural formation happens, I thought, what does one of these things have to do with another? Now, I was working on another project at the time, and I had a baby and then another baby. And so I set that project aside, but I didn't stop paying attention.

Because for about a year and a half, I had researched other Christian pastors, evangelical pastors: Mark Driscoll and Doug Wilson. And this was the heyday for this very macho, militaristic Christian masculinity. And then what I saw happening, even as I set it aside: for the next decade, one after another of the pastors who had been promoting this vision of militant masculinity became embroiled in scandal, abuse of power, sexual abuse, either directly or covering up for their friends who were the perpetrators.

And so it was October, 2016, as the Access Hollywood tapes released, and we saw how conservative White evangelical support stayed solid behind a self-proclaimed abuser. Everybody was asking, how could this be? And I knew that was the wrong question to ask, because I knew that they had been covering for abusers in their own churches, in their own communities, for decades.

Paul Raushenbush:

It's chilling, and it's like the piece of the puzzle, where you're like, oh, this is the central piece. You click it and you're like, oh, I see the whole picture now. And that's what it feels to me. What you were able to put together there.

And I was watching this a little bit further from the sidelines, because I'm not from the, whatever they call it, the bible-believing Christian, I'm hopelessly mainline. And but I was watching people like Mark Driscoll. In fact, I was working in Seattle at the time and you just saw this sense of… I mean, you see the videos. Last night when I was watching your film, I mean, it's mystifying to me: a video of a tank that comes out at one of these Christian… Whatever you call them. Revivals, I guess it's called a revival. That's a strange revival. A tank comes out and rolls over six cars. I don't know what the cars did to anybody, but this had a message, which was hard to comprehend from my vantage point, but that's what I saw.

You saw this from the sidelines. These people were like, first of all, it was always women have to submit. It was always, gay men are like really the worst because they've absented themselves from, really, their role, which is to be dominant males who are leading society somehow. You can't be that and gay.

I think that what your book put together really created this… It's a surround sound. It has a political implications, it has foreign policy implications. I want to talk about that in a little bit; but what you zero in on is - and honestly, I'm so grateful for it, because what your documentary, and I'm going to say the name again for everyone, because it is so important, For Our Daughters, Stories of Abuse, Betrayal, and Resistance in the Evangelical Church. It'll be available for streaming. And what you've done is zoom that in to what the implications were for the women who are in this community. And this is millions of women who are a part of the - however you want to describe it, bible-believing Christian movement in this country; we might call them Christian nationalists more broadly - and what the implications were for women who were living in that system.

This was something you uncovered as part of your book. So talk about that, and then let's talk about some of the people whose lives were really affected by this terrible abuse of power.

Kristin Du Mez:

Yeah. I had just been following stories. And about abuse, I'd been listening to women's voices, and most of these voices were on blogs. And every once in a while, local or regional media might pick up a story. And I just had been tracking this for years, not planning necessarily on writing a book. I was just paying attention.

And so when I realized, in the fall of 2016, that I needed to write this book, and I knew right away that these women's stories needed to be in that book. But I was concerned, frankly, about lawsuits and liability, because and this was before #MeToo, before the #ChurchToo movement, and so honestly, right when I knew I needed to write this book, I consulted a lawyer to get a preliminary understanding of: can I include these stories? And got the green light, kind of we'll cross that bridge when we come to it; and then #MeToo happened, and then #ChurchToo happened, and then the SBC investigation happened. And what I wrote at that time, when all of these things were coming to light, is very important that they were, these stories of horrific abuse; and equally horrific, large scale complicity, cover-up, from the top down.

And what I what I knew was that these stories had been out there. Women had been speaking. Survivors had been speaking out - and they were ridiculed and they were demonized and they were pushed out of their church spaces. And I watched it happen over and over again.

So when I wrote Jesus and John Wayne, the last chapter is on this abuse. And what I do is I ask, where did this come from? And I went into the theology. I went into the teachings about the submission, about masculine authority, about sex, about a woman's duty to submit to her husband sexually, about a “boys will be boys” mentality when it came to male sexual restraint, about how it was completely on the woman: if you were not married, to be so modest that you never tempt a man - because again, boys will be boys. And if you are a wife, it is your duty to fulfill your husband's every sexual need.

The result of all of this is if there is sexual misconduct abuse of any sort, there is always a woman to blame. And I saw these repeated patterns over and over again, victims blamed for their own assaults, even very young girls blamed for their own assaults because of the system to prop it up.

Paul Raushenbush:

And also, it can never be the man's fault. Over and over again. And I just have to say, one of the things - and I wrote this down when I was watching your great film, horrifically great, was the standing ovations when the men came forth and admitted to what they had done without any sort of actual atonement. It was just confession. It was like, hey I did this. How brave of you to say that you did this! While the woman is being reviled, and the man gets a standing ovation and a big hug from his daddy.

I'm sorry. I'm projecting. You know, all of these were introduced by more senior pastors. You did somethin’ wrong, son, you did somethin’ wrong, but now you're saying it, you're admitting it. There's no repercussions. In fact, they get elevated - and potentially to do something worse, which in one case it becomes worse.

And so I just thought that, when I wrote it down: standing ovations, what is it? And I have to say, every person in that room who was giving a standing ovation, I think in their heart they thought, okay we're helping this person with his repentance. But they weren't. They were actually affirming, again, his status, and I just found that absolutely chilling, and I'm still not convinced that any of the perpetrators, but those people who protected them, if they've ever really understood what they did.

Kristin Du Mez:

No. And this is why. Sure, in any community, there's a chance to have bad men doing bad things. There are going to be perpetrators throughout all of society. We know that. But inside these church spaces, what is so shocking is the way that quote unquote “good Christians” will consistently give cover to the abusers, protect them, demand forgiveness, and demonize and ostracize the victims.

This happens over and over again. And honestly, when I was doing research for the book, at first I thought, oh, this has to be an outlier. And then I came across another story, and another story, and another story. And so I could have chosen from so many stories to include in this film. I went with some of the most prominent survivors.

Jules Woodson, standing ovation story there. Tiffany Thigpen, another standing ovation story. And in her case, those who covered up were some of the most powerful men in the entire SBC, the Southern Baptist Convention, the biggest Protestant denomination in this country. Incredibly powerful organization. And then Krista Brown, of course, she has been at this for decades. And the reason I went with these prominent women is not just because they are so powerful and so articulate, but also because I did not want to bring any other survivor into this public space if they didn't know what was in store for them.

Because the treatment of survivors who speak out is absolutely brutal. And I will say, as somebody who's been speaking on this for years, now - and speaking on a lot of topics that can make people uncomfortable or even angry. There is nothing – nothing - that I can write on or speak on that brings the kind of hate into my inbox and hate coming at me on social media than when I call out the abuse of women at the hands of Christian men. Absolutely nothing comes close.

Paul Raushenbush:

And at the same time, there was a great moment in your film where one of the women went public in the Dallas Morning News about what had happened to her. And then she got email after email after email of other women who said, Oh my God, I thought I was alone. And I think this feeling of being alone contributes to this question, like, Oh, everybody's saying I did this. I was the perpetrator of my own abuse.

And then when you realize, Oh no! No, no, no, no, no. There's so many other women who have gone through this whole thing and were getting the same treatment. I think it's just so important. And again, I've been like four steps removed, I have to say, from this, but I have been observing, as someone who cares about religion in America, the - I don't know what to call it with the Southern Baptist Church - recognizing that things have happened.

And yet it seems like it's two steps forward, one step back, two steps back. I don't know. There is always this hesitancy to own up. It's similar with race. We were founded as an excuse for slavery as a denomination, which is true about the Southern… Should we do something about race? We should probably do something about race, but let's not do too much about race. And I feel like this even less so, because undergirding all of this is a theology. A theology that is consistent. None of that has changed. And so it's very hard to figure out how to change a system of abuse when you have a theology that continues to undergird it.

And you see all of these revivals, now, around the election, and still this warrior Christ. I don't want a peaceful Christ! I want a warrior Christ. These are actual things that people are saying, you know, cherry-picking a couple verses from Revelation and saying, okay, well this is what Jesus was really about. And so I'm curious how you view the efforts of the Southern Baptist Convention... This is not just Southern Baptists. This is much broader than that. But they are organized in such a way that they could do something about it. How have you watched that happen in the last, whatever, eight years? And what's your assessment of where they are at with this?

Kristin Du Mez:

What I've seen is there are many good people, and have been many good people, on the inside who have been awakened to this problem, and have stepped up and have tried to work for reform. And then they see what they're up against. And it is ruthless. You could see Russell Moore. What was his grave sin that got him, the most powerful man, arguably, in the SBC, that got him booted to the curb?

It was two things, really. He had misgivings about Donald Trump, and he said we need to address abuse within our ranks. Those two things got him completely and brutally ostracized, pushed out of his own denomination. Why? There are very powerful men who are invested in protecting their assets and in protecting their friends. And in some cases, men who are advocating against abuse reform - it comes out they themselves are abusers. And so this is just through and through.

We could look at Paul Pressler, one of the kind of founding members of this conservative takeover of the SBC. Paige Patterson. Look at the stories that have come out from those men in terms of abuse, and in terms of tolerating or refusing to deal with the abuse in their midst of perpetrating, in the case of Paul Pressler ,against young men.

And this story focuses on women, in particular - women and girls who are victims. But there are many, many victims in the SBC and in broader evangelicalism, boys, who were abused. And that brings in another whole set of complexities because of their anti-LGBTQ teachings that make it just an added shame for victims in these spaces to bring that forward. And honestly, that could be another film, series of books, to more fully reckon with that abuse and the legacy there.

Paul Raushenbush:

You drew the line, and it was just so important that you did: again, people from the outside, myself included, but I think the broader public, who are like, how can these people who say they’re bible-believing and have this strong moral core that they like to talk about, supporting someone like Donald Trump, who has shown himself to not be the exemplar. In fact, there was a time when he was the perfect foil for what you don't want to be in society.

But now they ascribe all kinds of things to him. Is he Cyrus? Who is he? But what is clear is, all of these things about… You know, he has been convicted of sexual abuse. He has been convicted of hush money to a sex worker. And he has also been on tape saying really terrible things. And then you say, Oh! With your research and with your bringing all of this to light, and with the theology and the kind of worldview that undergirds it, you say, Oh! Actually, that's not a bad thing at all, in some ways.

I think maybe for some women, but there's kind of a direct, Oh, okay, we get it. You're taking control. You're a man. I don't know,this is where it really is this extraordinary toxicity around what authority and you just get to take whatever you want. And this is undergirded by this idea of God has mandated this, according to a very, I would say, corrupted understanding of the gospel.

There is, for those who are wondering, in the film, there is a really good pastor, an older White man, who is brings up - I think it's so good, because that is the passage that I also look at - the temptation of Jesus to have control, to have power over all the nations. That's the devil's temptation of Jesus. That's the big temptation moment. You will be able to control everything.

And Jesus says, no. And I love that you did have this pastor, rejects all of this. But just to stay for a moment with this, if people are looking to understand how this broader religious community can support the candidacy of Donald Trump. I think you've unlocked it.

Kristin Du Mez:

Yeah. And if there's always a woman to blame and if women are blamed for their own abuse, they didn't deserve to be protected. And there's such an ends justifying the means mentality here. And part of this picture is understanding how - and this is what Jesus and John Wayne spells out - for decades, evangelical leaders have been stoking fear in the hearts of their followers: fear of secular humanists, fear of communism, fear of radical Islam, fear of Democrats… Just fill in the blanks. Feminists. There's always something to fear. And I came to see how, then, the fears that were produced were in many cases genuine, right? But they were manufactured in order to consolidate leaders’ power. And this is just a tried-and-true tactic.

In the case of abuse, then, you need to protect your protector - because this builds up this sense of well, the threat is so dire and is always so dire. And so that can justify any – really, any kind of of actions on your behalf. In fact, you welcome it. And that's why Donald Trump, when he appeared on the stage, as soon as they understood who he was and what he was going to do, he promised he would fight for them. He would protect them. They saw him as, in their words, their ultimate fighting champion.

And if you have somebody who's going to slay your enemies on your behalf, do you want somebody who's embodying the fruit of the spirit? Do you want somebody who takes Jesus’ words to heart? No, you want somebody who is going to slay the enemies. And so Donald Trump was perfect precisely because he did not embody those Christian virtues.

And, spoiler alert here. That pastor that you're talking about who appears at the end of the film - he's actually my own pastor. He's not some superstar big-platform person, which is why you haven't heard of him before. But when the director was talking about, we need to have some men's voices here. We had so many women's voices and we need to present the alternative, that this is not the only way to be a Christian. And Rachel Denhollander does that so well. They said, how about, could we get a pastor in here? And he named some of the kind of usual suspects. And I said, how about we just go with somebody who's actually really shaped my faith, my understanding of Christianity. And so that's where Pastor Len comes in.

Paul Raushenbush:

I love that. We’re about to come up on a very serious election, and it is not lost on you, I'm sure, that Donald Trump's opponent is a woman and a former prosecutor of abusers. And I'm just wondering how you feel this might be resonating among the broader community that you've been studying and looking at for so long.

It's not surprising that this is being portrayed as an apocalyptic moment for their champion. I'm just wondering how this is playing more broadly in the communities that you've been studying.

Kristin Du Mez:

Yeah. It was important to us to to address this political moment. And I will say, when I was writing Jesus and John Wayne several years ago, as I was doing the research, as I was fitting these pieces together, I kept looking at what was happening and I thought, oh, this can explain so much, right? All of the puzzlement, the questions of how could they, is it betrayal? Oh, no, no, no, no. Let me show you, right, there’s so much.

And I had the same feeling about this, these women's stories: that although they've been trying to raise awareness, they've also run into so many obstacles. And I thought it was really important to put their stories, in all of their power, in front of the country. In front of women, in front of Christian women in particular, in front of Christians, and just hear them and grapple with: how could this be allowed to happen. How could, even after these wrongs were exposed - and all of this, by the way, has been thoroughly vetted. Legally vetted, this is truth. How could this then persist? And then, what are we doing as Christians, as church members, perhaps, or even as voters, to perpetuate these systems that foster abuse.

And so I did not hesitate to make some direct connections to our current electoral choices. When you look at the Trump administration, when you look at Project 2025, when you look at who some of those authors are and you see how they are tightly connected to these Christian nationalist networks who teach precisely these teachings: masculine authority, patriarchy, female submission, control of women and control of women's bodies…

This is not just: oh, they use some of this language over here and they use some of that language over here. We can trace the networks connecting the system that fosters abuse in these church spaces with some of the very explicit plans that they would like to implement for our country. And so that's why it was important to us to amplify these women's voices and to put this out in front of the country, and in front of Christians, in advance of November.

Paul Raushenbush:

The documentary film is called For Our Daughters: Stories of Abuse, Betrayal, and Resistance in the Evangelical Church. What is the best way that people can find it?

Kristin Du Mez:

You can go to forourdaughtersfilm.com. It will be streaming from there. It will be on YouTube. And we also have it on a streaming platform. Details can be found at forourdaughtersfilm.com, that allows for group screenings, virtual screenings. And the reason we're putting it online instead of on a standard streaming platform is we want accessible to every single person, every woman who wants to see this. There's no barriers. This is not a for-profit movie. This is a labor of love, and we want everybody to have access to it.

We're hoping, too, that women will hold their own watch parties with their friends, with their church groups, and try to get these women's voices in front of as many people as possible - as a way to honor them, as a way to amplify their voices.

Paul Raushenbush:

This is forourdaughtersfilm.com. And on there, are there guides for conversation or anything that will be

Kristin Du Mez:

There are discussion guides, and resources, if you find yourself in these situations, and bios for all of the women who participated. And yes, you can go to forourdaughtersfilm.com and find all of these resources.

Paul Raushenbush:

Dr. Du Mez, thank you so much for taking this time with us on The State of Belief. It's such important work, and we're so grateful to you.

Kristin Du Mez:

Thank you so much for having me.