State of Belief

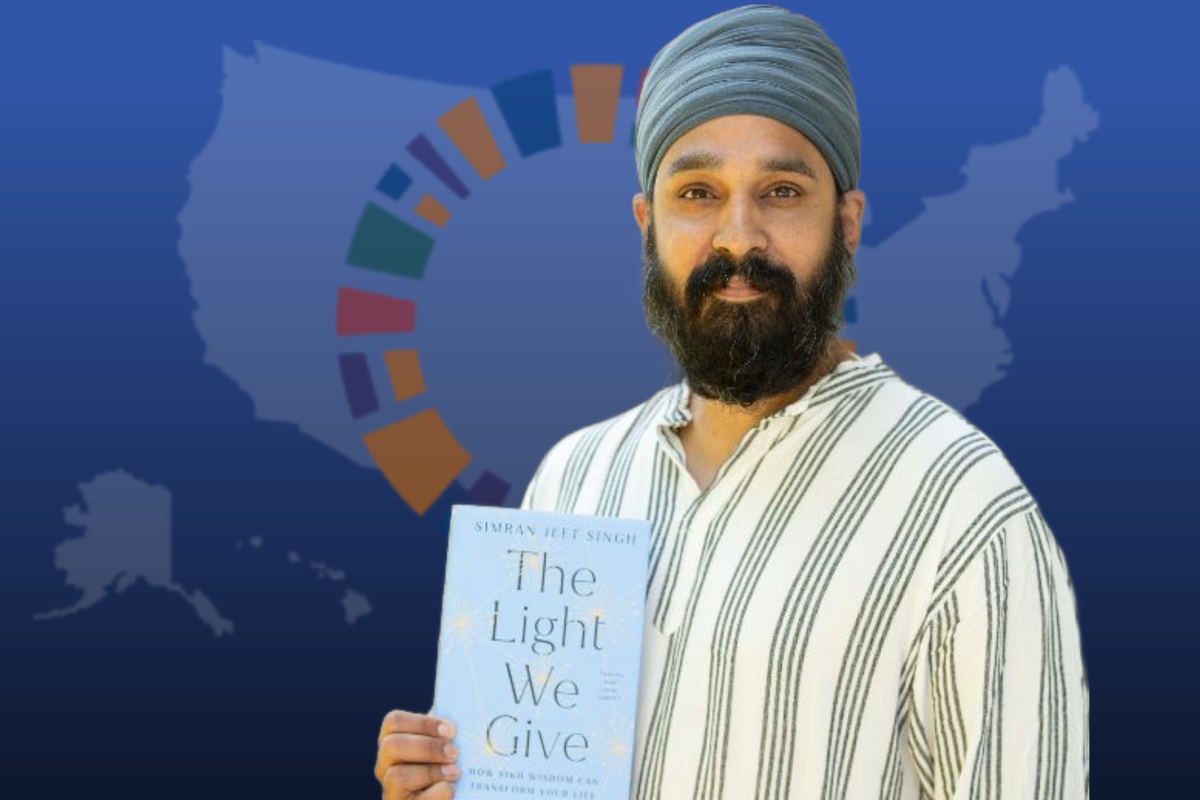

The Light We Give: Simran Jeet Singh on Courage and Community

What does courage look like on the ground? For many faith leaders and everyday citizens, it involves showing up despite risks, discomfort, or opposition. Dr. Simran Jeet Singh, scholar and activist, describes courage rooted in love and fearlessness—values encoded in Sikh teachings like nirpo (fearlessness) and nirvad (without hatred).

Simran reflects that true bravery is not about bravado or self-assertion but about steadfastly choosing love over hatred, even when faced with hate or violence. For example, during a clergy-led protest in Minnesota, ordinary people—clergy, community members, and even those with vulnerabilities—stood on the front lines, committed to protecting their neighbors and advocating for justice. Their actions exemplify that small, consistent acts of love and solidarity are the most powerful resistance to authoritarian tactics.

This kind of courage asks us to stand with neighbors in difficult moments, practice humility and listen deeply, and act lovingly in the face of fear.

The author of the best-selling book The Light We Give: How Sikh Wisdom Can Transform Your Life, Simran shares a story from Sikh tradition that struck me: a tiny lantern flickering in the darkness, not to fix everything but to let a little light shine. When enough of those lanterns light up, the darkness begins to lift. It’s a simple, powerful lesson: humility, love, and perseverance are acts of courage.

Thursday, Feb. 5th was the annual National Prayer Breakfast in Washington, DC. This purportedly apolitical event has turned into “one big farce,” in the words of US Rep. Jim Clyburn. He spoke with us exclusively about his reasons for not attending the breakfast, and you’ll hear that along with the comments of other members of Congress who have also made the difficult decision to absent themselves: Rep. Jared Huffman, Rep. Lucy McBath, and then Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, who is also an ordained minister. Host Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush was invited to share thoughts about the Christian Nationalist takeover of the National Prayer Breakfast on C-Span, and you’ll hear an excerpt of that on this week’s show, as well.

More about Simran Jeet Singh

Dr. Simran Jeet Singh is a scholar, educator, writer and activist, who focuses on religion and racism. Simran is a professor at the historic Union Theological Seminary and Senior Advisor for the Aspen Institute’s Religion & Society Program, a columnist for the Religion News Service, and a contributor for TIME Magazine. A Texas native, Simran is the author of several important books, including the national best-seller The Light We Give: How Sikh Wisdom Can Transform Your Life, and his Substack is titled, More of This, Please. Simran also hosts Wisdom & Practice, a new podcast by The Aspen Institute and PRX. He's working on a new television series titled Undivided. Learn more on Simran's Instagram.

Transcript

REV. PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH, HOST:

Dr. Simran Jeet Singh is a scholar, educator, writer, and activist who focuses on religion, diversity, and racism. Simran is a professor at the historic Union Theological Seminary, my alma mater, and a senior advisor for the Aspen Institute's Religion and Society Program.

He's a columnist for the Religion News Service and a contributor for Time Magazine. He's a Texas native and the author of several important books, including the national bestseller, The Light We Give: How Sikh Wisdom Can Transform Your Life, and his Substack is titled More of This, Please. Simran also hosts Wisdom and Practice, a new podcast from the Aspen Institute and PRX.

My friend, welcome back to The State of Belief!

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

Thanks Paul, it's good to be with you.

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

So this is a time when many of us are assessing how we feel as Americans, as people of our faith tradition, as… You know, we're both fathers. I'm just doing a check-in to see how your heart is today.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

I appreciate that. The heart is full. Full and challenged, maybe is the best way to describe it. Life is amazing in so many ways. I have these kids that you mentioned and they bring a lot of joy, and also lot of important reminders to me about what really matters and how to stay grounded.

But then the other side of that is the challenge. It feels like things, every day, are harder and worse, and that's a commentary on the country and our world. And so the challenge, it never really seems to go away, does it?

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

I was just talking to another friend who's really in the center of a lot of this, and we were exchanging some techniques, and just about what does it mean to continue to move forward in love with a sense of endurance and perseverance, recognizing that we're not going to get out of this quickly? We're going to have to go through it and we're going to have to find ways to maintain our broken hearts and hold those, and also just continued resilience and fortifying one another. So I actually want to pause for a moment and see if you could offer us any of the important reminders that your children, perhaps, have inspired in your spirit and your soul. How are ways that they bring you back to something beautiful? Because we just need that. We need that.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

I'm thinking about a conversation that I just had with my girls about the violence in Minnesota. And it's hard. My kids are pretty young and I'm trying to figure out what's an appropriate way to explain to them what's happening in our country. I think the funny thing about that conversation was that every time I tried to explain it logically, their response would be: but that doesn't make any sense.

And I think part of what I gained from that conversation was the understanding - and faith teaches us this too - that logic isn't always the best way to understand the world and to live in this world. And maybe to let that go a little bit and say, it is true that sometimes our world doesn't make sense and how we behave doesn't make sense and how we treat one another doesn't make sense. And to relieve ourselves of the attempts to constantly intellectualize, to evaluate, to analyze it and to really just be.

And so there was this moment that I had when I was sharing this with them that reminded me of something that my faith teaches me, as a Sikh: that rationalization is not the path to liberation. And so to disabuse ourselves of that notion is actually liberation.

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

Wow, that is really interesting. My son joins Brad, my husband, in watching PBS NewsHour every week. And so he really is interested in this as, like, what does this mean for our country? And how is this allowed to happen? I think those are the questions that we're all asking.

And for those of us well versed in the history of this country, this is not the first time that there have been patrols snatching people and doing terrible things. So there is a part of our DNA that that has this within it. And there is another part of our DNA that has resisted it. And I think figuring out ways that, especially for those of us in religious communities, can tap into the part of our faith communities and faith wisdom that allows us to continue to move forward and work towards a country where what is happening now in Minnesota and all over the country becomes something that we talk about in history terms rather than current terms.

I am curious, you are now a professor at Union, and that is very exciting to me as someone who's a very proud graduate and someone who now is coming up, gosh, I will have graduated this year 30 years ago. That's wild to think about. I hadn't really put together that this is a kind of a big year. But I will say, in a welcomed way, Union at that point was just dipping its toes into the idea of, what does it mean to teach from other traditions and broadly?

What are you teaching this year and how are your students reacting in this moment? People who are in faith formation - or maybe it's not faith formation; formation writ large, let me put it that way.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

So you're right that Union has been expanding its offerings into what it calls “inter-religious engagement.” So moving from its historic Christian roots into other traditions. The two primary tracks currently are around Buddhism and inter-religious engagement, and Islam. And so I teach in those traditions. It's sort of my own training as a scholar and historian. This semester, I'm teaching a course called “Islam in the Americas.” So it's looking at not just the history, but also the present of Muslims in these communities.

And I'm teaching a course called Global Buddhist Histories. And so that is an attempt, in a humble way, an attempt to capture the broad swath of Buddhism around the globe across time. It's a lot to cover, but it's an intro level class. It's really fun. I've been teaching that pretty consistently the last few years. So I teach a lot on Buddhist history, Islamic history, a little bit here and there on Sikh history and tradition. And I had a chance to teach some of that this January. So it cuts across a lot of different experiences. I really enjoy it.

And just one reflection on what I'm thinking about now and something you just shared, sometimes history can actually be a very nice companion in difficult times, because it is easy to get near-sighted and narrow-minded around, you know, this is the worst thing that's ever happened in the world. And we often feel that, whether it's around immigration issues or violence or weather - I mean, it's so easy to feel like we have it the worst ever. it can help sometimes to scale back a little bit and zoom out and say, okay, other people have dealt with these kinds of issues. They've made it through. Maybe I can too. And so I found a lot of solace in studying history, as well.

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

That's so interesting. Brad wrote a book about Rumi, the Sufi poet Rumi. I think what most people don't realize is that Rumi lived in a cataclysmic time when the caliphate was destroyed and his whole family was fleeing the Mongols that destroyed city after city after city. His whole life was lived in the context of absolute uncertainty and, really, destruction of what had been the known Muslim world in some ways. And out of that comes this poetry. People kind of wanted, like: I assumed he lived in the 70s in California and wrote these really sweet love poems… But actually, it's more powerful to understand what's actually going on around.

And I think we're in a moment where, I will say from my vantage point, that there are horrific things happening. But if I've learned anything from going to Minnesota in the past weeks and learning from people on the ground there - but also all across the country - the level of engagement and people who want to show up right now and do something, and be part of something and really view it as the opportunity to create something is powerful in this moment that will last into the future. I do think that that's perhaps one of the things that we can hold on to and also expand and get excited, really have it draw us, that it's drawing us, a calling or a vocation. I do feel called to this moment. I don't use that language that much, but I do feel like something is calling me to show up with courage right now.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

What did that feel like in Minnesota when you were there? A lot of us were watching online and trying to get a sense of the magnitude, both in terms of how many people were there, but also how significant it was. When you're describing the hope you feel coming out of Minnesota, what was that like?

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

Well, I was invited there by a group called March. Actually, I had four Minnesota Christian clergy on this show to talk about what was happening on the ground. And it was very interesting, at the end of that show, they said, hey, we're inviting clergy to come be with us, to witness with us, to learn and also add your voice and witness. You should come, Paul, you should come. And I was kind of like, yeah, another thing that I will probably not do.

But then the call went out, you know, you're always like, where should I be putting myself? I don't know. The call went out and all of a sudden it was really clear: it was like, oh, I've got to go. I've got to go. And people around me, my team was like, you've got to be there. And so this group - you know, there were many groups, by the way, there's Isaiah, there's all sorts of faith organizing happening there. Our friend Najiba Sayyid is part of that, and she was on the show recently talking about Minnesota.

But this group called March started, actually, as a queer organization around same-sex marriage passage. It brought together this coalition of people. After some of the racist murders, including George Floyd, people said, we need you to come alongside us. And they changed their name to March, which has anti-racism in its name, and it's both a pro-queer but also anti-racist organizing group. And they put out this call, and they said at the beginning when they gathered us the first day, they said, we expected maybe 200 people to show up. Within a day, a thousand people had RSVPed saying they were coming. And that's what I mean.

And by the way, it wasn't like they were paying our way. They were trying to make it as possible, some home stays and things like that. But it was really, come if you can. And people were like, I can and I will. And so it was very powerful to, first of all, I had heard it in a State of Belief podcast, but then to be on the ground and show up the first day in this huge church which was absolutely filled with clergy, all clergy and singing songs and just feeling everyone felt called to be there and to follow the insight, the direction of the people on the ground, learn, share. So it was really, really amazing.

Then by noon we were going out and on ICE watches. And they'd given us training, they'd given us whistles, but they said, if this feels messy, if this feels uncertain, if this feels like you're not completely prepared for what you might see, welcome to doing the work in Minnesota, because that's what we always feel. And I think that was really important to say because, you know, the idea of: there's the experts who will handle this rather than… This is us. This is us who has to do it. And that was really important for us to hear. And throughout the next day were actions.

I'll say one other really powerful moment for me, which was very humbling, at the beginning of the afternoon, they said, okay, you know about this action at the Minneapolis Airport - Did you see any of the photos? - So there was an action and they said: we just need to say, we will be calling on people who want to be arrested. And just so you know, this is a federal crime. So we will not be able to assure anything about what will happen to you after you're arrested.

And I was like, whoa, okay. I was not there to get arrested for lots of reasons. And then they said, but if you’re interested in this action, please leave the sanctuary now. We're going to go and do a training on that, particularly. The flood of clergy. I mean, it was 250, 300 clergy filed out. And not to be ageist or anything, they're kind of my age but older, just saying, okay, this is where I'm going tp put my body right now. And I can and I will. And not everybody can do that right now because of their own vulnerabilities and things like that.

I have been seeing this, Simran, for the past year. The Interfaith Alliance has exploded this year. We started with eight affiliates, we're now at almost 40. People want to do something, they want to show up. And so I think that that was part of the lesson of Minnesota is that they are showing up for one another, and the organization and faith leaders alongside other leaders. It's not like faith is saying, well, we're the ones who have to do this. They're saying everybody is coordinated.

I did a pilgrimage from George Floyd Square to Renee Good's memorial. A lot of this organizing came out of that. And it was really powerful. The person who walked us through George Floyd Square, she said, neighbors are people we choose to be in community with. And I was like, wow, that. You know, when Jesus says, love your neighbor, it's like, I choose to be in community with you. And I think a lot of what is happening in Minnesota is about people choosing to be in community. And so I was incredibly moved.

And then it turns out ICE was following the bus that was holding the clergy. And then they did a detour and attacked a car that was behind us that was legal watchers. Broke the window, these two women came in with shards of glass in their face. And so it's very real, very present, and yet the incredible people on the ground. So, sorry, that was a long answer to your kind question, but obviously I was very moved by it – but I've been moved across the country, this year, by faith communities, faith leaders, and figuring out ways to show up. And we will show up.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

And what does it say to you as you're watching clergy members put their lives on the line, right? Being willing to make real sacrifices and take real risks in order to stand up for what they believe in? Is there some larger message that you are taking away from that or that you hope other people are witnessing as they see it from afar?

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

Well, I think it's: everybody has to assess what they can do and do that thing. Like I said, a lot of the people who were arrested in, older white clergy who kind of felt like, okay, I have just about as much privilege as you can have in this country. And so let me see what I can do. And other people in other communities are doing food assistance to those people who can't leave their homes because they're worried that they will get snatched up. But we should all be thinking: what can we do right now? And I think the making the choice of what can we do, and how will we remember this time about what we can do and what we feel called to do - I feel like, right now, it all feels very clear.

I think the administration, they are very clear about, they're trying to control the population and with a very particular agenda rooted in White Christian Nationalism. And the rest of us have to figure out what we can do with the resources we have, meeting this moment - and that's what it says to me.

Maybe I can take this off me a little bit. You had this amazing book that really hit, and it has a title that I think is relevant to this moment, The Light We Give: How Sikh Wisdom Can Transform Your Life. I don't know that you were writing it with this kind of moment in mind, but certainly the question of what kind of light can we give in a shadowed moment like this, I think, is the right question to ask.

How do you feel like the reflection you've done on your own tradition is helping you translate where to go and what to do, and how you convey that to your students and all the people you talk to?

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

It does feel like the big question of our times. Yes, I didn't have these particular issues in mind when I was writing the book, but there was a sense, having lived in this world and studied history and different cultures all around, these moments have always been there and they will always continue to be there.

And so I find that as I travel around the country and talk to people, especially young people, there is a sense of nihilism, of what's the point of trying if I can't fix everything. I mean, I'll admit that I resonate with that feeling. I often feel that way of throwing my hands up in the air and saying, what's the point? This whole world is on fire. I think what I've learned through Sikh teachings, one of the biggest lessons that I've taken away and applied in situations like ours today is that if we come in with the expectation that we will fix everything and that we can fix everything, we will always end up dissatisfied.

And there's a certain level of, I love the aspiration and I don't want us to give that up, but there is no balance with the pragmatism, right? Can we be realistic in understanding what, like you were saying earlier, what is ours to do? What can we actually accomplish? And finding the right balance between the world we want to create and the world we have.

And so there's this story that I share at the beginning of the book that comes from a Sikh human rights activist. And it's an old Punjabi fable about the first night that the sun was setting. And the sun is going down and people are stressed. They're worried, will we ever have light again?

Will we be cold? Will we have food? All these questions are going across their minds. And across the fields, there's a small lantern that lifts up its wick and says, I challenge the darkness. From my little corner, I'll provide the light that I can.

And it's through this single action that a number of other lanterns decide to flick on their wicks as well. And then there's brilliance. The sun is not there. It's not visible. But the light is, and I love this story because of two things it tells me. I mean, it tells me a lot, but there are two things that are really standing out in this moment. One is,there was no intention of that first lantern to fix everything. It was just, you know, here's what I can do from my little corner of the world.

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

Yeah, the lantern wasn't saying, now I'm the sun.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

Exactly, exactly. there's again that realism to it. The self-awareness of, here's what I can do with a level of humility. Not the arrogance of, let me fix everything, let me become the sun. And the second piece is, and I think we get this wrong too often in this culture, by just doing the thing, you can inspire others to follow. And instead, so often we end up preaching or telling people what they should do or telling them why they're wrong. How much of our culture is just that, right? Pointing our fingers at people we disagree with. And instead this lantern just says, let me do what I think I need to do and see what happens.

And I just think about that so often, especially as someone who is trained as a scholar who writes for a living, who speaks for a living. It's so easy for a lot of us - and for me especially - to kind of fall into the finger-pointing and problematizing and blaming institutions or blaming leaders. And I'm as frustrated as anyone with that. It hasn't really gotten us very far. And so this story is one that I keep returning to us. Okay, what is mine to do? How do I create a small piece of change that transforms - doesn't fix the world, but transforms how I experience the world - and the people around me might benefit, too.

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

It reminded me of the Jesus, kind of, not hiding your light under a bushel. Me not hiding my light doesn't mean that I'm going to light the whole world. It just means, I do have a light. It's acknowledging that we each have a light. And I think it's really important. And, you know, bringing some heat and some hope, I think it's huge. And especially in a moment where, really, the best tool of authoritarianism is to make people feel like they don't have a light and feel like we're going to enforce what we're going to enforce and this is not up to you anymore. so I think that it's very powerful.

I also want to talk to you about something that's really exciting. I know you've been really committed to a documentary series called Undivided. Can you tell our listeners a little bit about that and how they might learn about it, and any way they might support it?

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

I appreciate you remembering. I'm impressed you remember. You're right that it's not a secret, but it has been somewhat under wraps as we work through production. But I guess in a way it's my version of bringing the light into the world in the way that I can. And it really stems from this experience I have of growing up in this country as a Sikh, and just wishing people knew who I was and realizing that my life could be so much easier and so much better if people just knew a little bit about me.

And so this has animated my work in the world. It's why I teach what I teach at Union. It's not just about my own community, but it's about other religious traditions, too. And this TV show has essentially been, at least in my view, the next step towards trying to bring this culture change to scale. So in a classroom, I might get 10, 20 students. If you write a book, you might get, I don't know, these days maybe like 10, 20 readers. You might get a few more than you do in class. But it feels to me that where we are culturally right now, like...

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

Stop bragging, stop bragging.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

Everybody's watching videos, everybody's watching TV and Netflix and movies and so on; and so what would it look like to meet people where they are? It's not my brainchild; it's a friend of mine, Jack Gordon, who's the director who brought the idea to me originally. But it's essentially premised on this idea of: what would our country look like if instead of making assumptions about one another we actually learned our stories.

And so the first season we spend time with different communities: Muslims, Jews, Latter-day Saints, Sikhs, and members of the Black church. And the question we're essentially asking is, how do these different communities fit into the American story in ways that we might not have imagined or assumed otherwise? And I'll tell you, it's been really fun, going through the process and learning how a new industry works. It's been challenging at times, but it's really been transformative to me. Even as someone who's trained as a scholar and historian of religion, I learned so much.

I learned a ton, and I'm realizing that if I didn't know some of these basic stories, if I'd never heard them before in all of my research, then what are the chances other Americans have? And so it feels so rewarding to be able to put these together.

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

I love that. Let me ask you this. Do you have anything on your social media channels? Because that's why I think I saw some of it. Are you on Instagram?

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

I do. Yeah, I have a trailer on there. We have a trailer for a couple of the episodes, I believe.

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

Good. That's where you get more than 10 or 12. What is your Instagram handle?

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

It's Sikhprof, S-I-K-H-P-R-O-F.

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

That's right. S-I-K-H-P-R-O-F, Instagram. That's amazing. You know, one thing I just want to spark a memory of, the terrible days after Oak Creek and the terrible attack by a Christian Nationalist on their Sikh community there. A lot of the mainstream press and a lot of maybe well-meaning people were like: but these people are not Muslims. They're not the problem. And you came out really strongly at that time and were like, that's not what this is about.

It's not us differentiating ourselves from Muslims or anything. It's about, actually, no one should be receiving this kind of animosity. And you used your platform and your voice in a really powerful way at that time. And I think telling these stories is a continuation that everyone has a right to their stories being known. And especially for those of us living in this country to understand that our diversity goes deep. It's not some sort of frosting on the top of a Christian cake. Actually, everything is baked in and you can't really have America without these diverse religious traditions. so I just think this feels very consistent with the way you've shown up since you've become a public voice.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

I appreciate that. It is an attempt for me to follow the way that I understand Sikh teachings. And, you know, Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, never announced that he had exclusive access to enlightenment. He said, enlightenment is for everyone and there are many paths. And so there is a very pluralistic vision that I think cuts against models like American capitalism. The scarcity model that says: there's only enough for some of us and not for all of us. And I don't see the world that way. I don't want to see the world that way. And so in some ways you could even think about this outlook as a form of resistance to insist that, you know, I am here for all of you, even if you're not all here for me.

And thinking back to that lantern and even your description of your time in Minnesota, these examples, these moments, they might model for other people how they might approach it, too. And even still, that's not the point. The point is to do what's right as I understand it and my tradition tells me, and to hope that I can at least transform my life and the people around me. And if that changes other people, as well, I would welcome that. I would love to live in a world where there's that kind of openness and care for people beyond identity and difference.

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

Before we wrap up, I did want to highlight a couple other books that you've written. They actually are lovely because they span from a children's book, but also a book that really celebrates someone who is very old and running marathons and an inspiration. Can you talk about those? It's lovely because you're a storyteller in the best academic tradition, I think. And talk about those two books and how they fit together, just so our listeners could know the resources that are out there for learning more - not just about, what does Sikhism teach, but also the lives of people, imagined or real.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

Thank you for asking. The first children's book that I did was called Faux Jessing Keeps Going. It was inspired by my running hero, who is the oldest person to ever run a marathon. And my dream was always to write books for kids that featured Sikh characters, because that's what I had always wanted. But it was when I met Faux Jessing and realized how much more I could learn from him aside from what he accomplished… You know, he challenged me.

Maybe the way to say it is, I assumed that because he was a Sikh, we would have everything in common - the same kind of assumption that other people might make about me, I was making about myself because I didn't know that many Sikhs growing up. And I got to know him and I realized so many of his life experiences challenged my assumptions. He wasn't literate. He never learned to read or write. He had a disability. He was older. All of these things challenged my ideas of what a hero could be. And it was in overcoming those assumptions through knowing him that I realized there was so much that I wanted to share with kids. So that's that story, and I love that.

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

That's an important lesson for kids to learn, the idea of what constitutes a whole person and a person we can look up to and learn from. And what can a hero be when you strip a lot of the assumptions about what a hero has to be? And I just think that that's a very universal. It's, of course, rooted in the particular, which is the best of all these kind of stories, but it's a universal lesson.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

It really is. you know, I think what I love about it is it does that work for children, but it also does that work for adults, right? For me, I was in my thirties when I had to engage with my own assumptions about literacy and intelligence. I just had always learned in this culture that smart people - based on a meritocracy model - smart people know how to read, and people who aren't smart don't know. And it's that simple. it was so wrong, but I wouldn't have ever known it until I got to know him. And you know, how many of us get that opportunity? So trying to bring that through a book felt really important.

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

Well, it was beautiful. Then I think a lot of people started to see him. And I think it was just the basics also of like… Okay, I'm 61 now, which feels very old. And I've already just said, well, I guess my marathon days are behind me. And I'm like, okay, well, maybe think again. I know you have a little bit of a bad knee, but not really. So, the things that I'm already saying I can't do, I do, anyway, that is inspiring. And your work is so inspiring.

I guess you could call it a virtue or characteristic that we're talking a lot about, to help imagine it or reimagine it, is courage. And I am curious what your take on courage is; and you personally, or if there's Sikh wisdom on it, what does courage look like right now in your understanding?

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

I love it. In the Sikh scripture, there's a composition at the very beginning that recurs repeatedly, that outlines the basic qualities of divinity. And in that outline, the fourth word is fearlessness, nirpo, and the fifth word is nirvad, without hatred. And those two don't always feel like they go hand in hand.

But then there's a teaching from the ninth prophet where he says, [quote in Punjabi], that the truly wise people are the ones who understand that we should not fear anyone, nor should we incite fear in anyone. And I struggle with that because in a moment like this one, it feels like in the wake of terror, the most intuitive response is a forceful one, one that mimics the kind of violence that's being enacted already,. So if one side is being violent and hateful and suppressive, wouldn't we just do the same thing in return? And it's hard not to fall into that. How do you not?

And I think the teaching here from Sikh wisdom is: can you find a different way of engaging that doesn't fall into flight or fight? Where you're not cowering, y ou're not giving up, you're fearless, but you're not acting out of hatred, you're acting out of love. And so that to me is the middle path of religious philosophy. It's also the hard one. It's much easier to either give up, as we were talking about before, or to simply fight back. And so courage to me is to remain steadfast in that commitment of no fear and no hatred. Love in the wake of hatred so that we're creating a different kind of response.

PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH:

I think that is perfect. You know, the root of the word courage is core, which is heart, which is love. And so what you just described is another way of getting at that. Courage is not violent. It's not bravado. It's essentially showing up with love, and insisting on showing up with love. And that's incredible.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

Yeah, which is scary. As you were describing your time in Minnesota, it takes real risk, there are vulnerabilities involved, sacrifice - but what is more courageous than showing up in that way? I mean, I'm just so touched by that example that you shared.

Dr. Simran Jeet Singh is a professor at Union Theological Seminary and the bestselling author of The Light We Give: How Sikh Wisdom Can Transform Your Life. The new documentary TV series, Undivided, is coming very soon. Follow Simran at SickProfessor at Instagram.

Simran, thank you so much for being with us here today on The State of Belief, and for all you are doing to let your light shine, permitting all of us to let our light shine.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH:

Thank you, Paul. Good to be with you.

Jewish-Muslim Solidarity: Moral Witness in Pressing Times

Highlights from a Capitol Hill briefing on Jewish-Muslim solidarity as a defense against authoritarianism, featuring prominent Muslim and Jewish leaders and lawmakers. With discussion and inspiration from host Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush and interfaith organizer Maggie Siddiqi.

We The People v Trump with Democracy Forward's Skye Perryman

Host Paul Brandeis Raushenbush talks with Democracy Forward President and CEO Skye Perryman about the first year of the second Trump administration. Skye describes how, amid a flood of policies and orders emanating from the White House, Democracy Forward's attorneys have brought many hundreds of challenges in court - and have prevailed in a great majority of them.

Courage in Community: Minnesota Faith Leaders Respond to ICE Crisis

Host Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush talks with four Minnesota faith leaders on the ground defending their communities against ICE attacks: Rev. Susie Hayward, Rev. Dr. Rebecca Voelkel, Rev. Jim Bear Jacobs, and Rev. Dr. Jia Starr Brown.