State of Belief

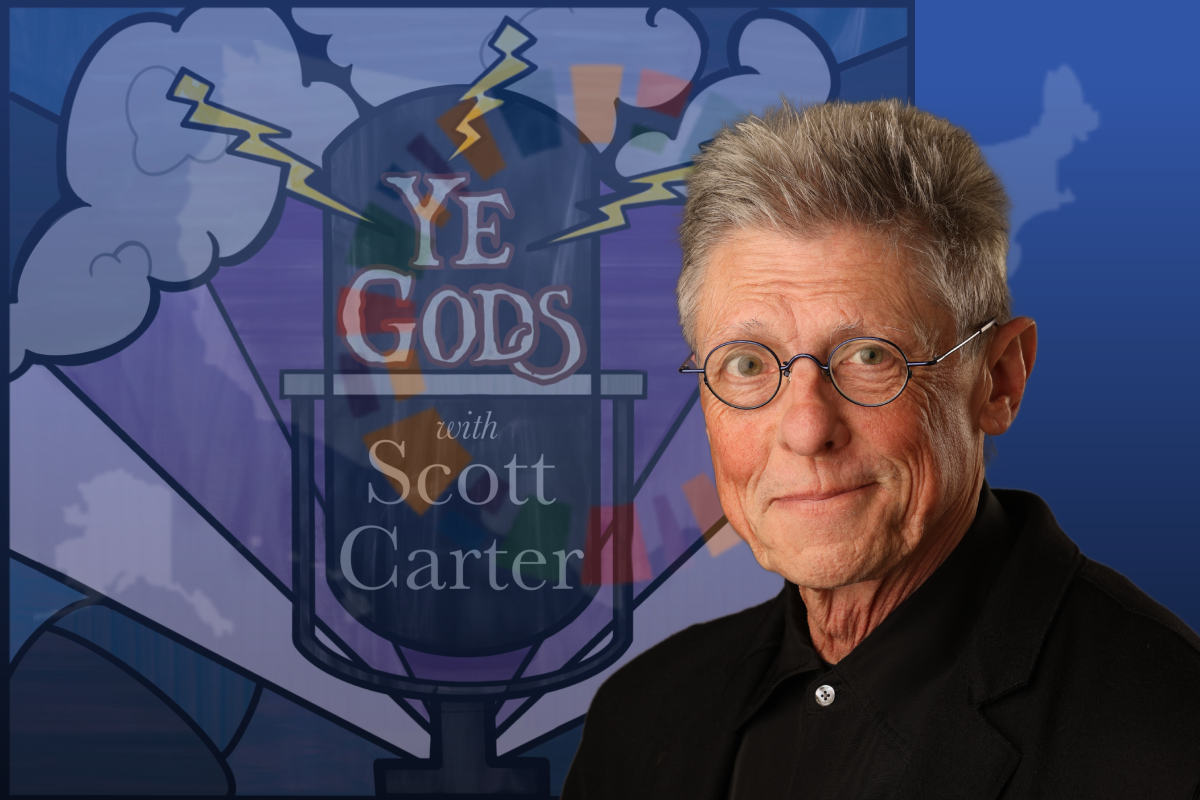

Ye Gods: Scott Carter's Journey from Comedy to Spiritual Exploration

This week The State of Belief features the fascinating Scott Carter, creator, executive producer, and host of the Ye Gods with Scott Carter podcast. In this episode, host Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush and Scott explore intersections of belief, doubt, and the moral codes that guide us. Notable ideas include:

- The Power of Intentional Curiosity: Scott shares his transformative journey following a near-death experience due to asthma. This epiphany moment led him to make a profound commitment: to engage openly with discussions about religion and spirituality without sarcasm or dismissal. His intentional curiosity opened doors to understanding diverse beliefs and perspectives, showing that being open-hearted can lead to deeper connections and insights.

-

- Art as a Spiritual Medium: Throughout the conversation, Scott emphasizes the role of art in exploring spirituality. He believes that creativity can serve as a powerful conduit for understanding and expressing our beliefs. Whether through theater, comedy, or storytelling, art allows us to engage with complex themes of existence and morality.

-

- Navigating Life's Challenges with Compassion: Scott's experiences in the competitive world of television, particularly on shows like Politically Incorrect, taught him the importance of compassion in every interaction. He shares how he strives to treat everyone—guests, colleagues, and audiences—with respect and love.

Be sure to hear this enlightening episode as we explore these themes and more! Scott’s insights are not only thought-provoking but also serve as a guide for navigating our own beliefs and interactions in a complex world.

More About Scott Carter and Ye Gods

Scott Carter is the creator, executive producer, and host of the Ye Gods with Scott Carter podcast, where he invites comedians, writers, thinkers, and artists to talk about belief, doubt, and the moral codes that guide them.

Scott has 21 Emmy nominations and many, many industry awards for his work in television, where he served as producer and writer for shows like Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher and Real Time with Bill Maher. He's been a stand-up comedian. He's also a playwright whose works cover culture, spirituality, and storytelling. They've been produced in cities all across the US and abroad.

The Ye Gods podcast gets into the spiritual beliefs and guiding principles of a variety of guests, going in-depth with notable individuals from various fields with no judgment and no agenda. Ye Gods is created with Southwest Florida's WGCU Public Media and is distributed by the NPR Network.

Transcript

REV. PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH, HOST:

Scott Carter is the creator, executive producer, and host of the Ye Gods with Scott Carter podcast, where he invites comedians, writers, thinkers, and artists to talk about belief, doubt, and the moral codes that guide them.

Scott has 21 Emmy nominations and many, many industry awards for his work in television, where he served as producer and writer for shows like Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher and Real Time with Bill Maher. He's been a stand-up comedian. He's also a playwright whose works cover culture, spirituality, and storytelling. They've been produced in cities all across the US and abroad.

The Ye Gods podcast gets into the spiritual beliefs and guiding principles of a variety of guests, going in depth with notable individuals from various fields with no judgment and no agenda. That sounds refreshing. Ye Gods is created with Southwest Florida's WGCU Public Media and is distributed by the NPR Network.

Boy am I glad to welcome Scott Carter to The State of Belief!

SCOTT CARTER, GUEST:

Paul, I am so glad to be here today - and I'm looking for a publicist and I think if you could assure that every intro was as complimentary as this one was, I think you have a job ahead of you.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

I feel like I need to move to L.A. because the last person who said that to me was Rob Reiner after I introduced him about his great documentary about Christian Nationalism. He was like, you know, maybe you should be our publicist. I was like, Rob, I am so available for that. It hasn't come through. I’m still president of Interfaith Alliance, but maybe there's a future for me somewhere. Listen, I'm so excited about Ye Gods –congratulations. This is such an important show. Tell us, first of all, why you wanted to do this kind of show, given your incredible track record. You could do so many things. You chose Ye Gods, which really goes into moral codes, beliefs, disbeliefs, all of that. I'm excited by this. Tell us why you decided to do it.

SCOTT CARTER:

Well this all starts back many, many decades ago in New York. I'm a lifelong asthmatic I've been asthmatic since the age of 2. And in fact I was born in Kansas City; my family moved to Arizona when I was 8 because in those days they thought that asthmatics had a better chance of surviving in the desert in the dry desert pizza oven air.

And that may have been true at some point, but there has been so much pollution in a lot of these formerly healthy sites that I don't think it's a cure for anyone anymore. I hope I don't get in trouble with their chamber of commerce. But so I became a playwright with a group in Tucson, Arizona, at the offshoot from the University of Arizona Drama Department that I helped found over 50 years ago - and it is still operating today.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Wow, what is the name of that troupe? What is the name of it?

SCOTT CARTER:

It’s called the Invisible Theater. In the first 3 or 4 years we did only original plays, than many of the writers left and it became an actors’ theater. But it's still a place where I've gone back to every once in a while to do monologues or to have revivals of old plays or readings of new plays. And so I went to New York, I tried to be a playwright in New York, but when I got there - this is the late 70's - everybody wanted a one-set, two-character play on some social justice theme. And I only had these elaborate 10, 15, 20 people plays with a hundred different locales because at the Invisible Theater, everybody wanted to be a part of our production in town. We were the hottest thing in town. So we could write plays and have huge casts.

So my backup, then, eventually, was to become a standup. so in 1987, I was a standup, barely surviving. I was not a great standup. I was more intelligent than funny, and more respected than I was amusing.

And anyway, I had a near-near death asthma attack in June of 1987. And I've been, like a lot of other comics, some of whom I've worked with for years who are either despising of religion, some are belligerent atheists. And I was not quite in that group, but I thought that if there's a God, why do I wake up wheezing most nights? Why do I spend a lot of my time in emergency rooms? And so I had this near-death attack. I was at my new girlfriend's apartment on 54th Street. I woke up, could not breathe, took pills, they had no impact, took puffs of my inhaler, my rescue inhaler, it had no help. So eventually she called 911. Paramedics came. They got me on a stretcher to an ambulance. It was a Sunday afternoon and we had to go through the Second Avenue street fair in order to get to Bellevue.

I got to the emergency room and after a few minutes, one of the doctors came up behind me and whispered in my ear, you're not going to die. And I remember thinking, okay, I will take your word for this. And luckily for me, the head of the chest lungs department, a doctor named Frank Adams, was on call that afternoon. And after I began to get treatments and I felt better and I was kind of back to normal - the place where normally I would then be going back to my apartment, heading home - he said, you know, you've been like a person trying to drive across country in second gear. You have been on a compromised foundation of health, and so I'm going to insist that you not go home now. That you stay in the hospital for the next week and I want to raise you to a new base level of health. And then every three months, I want you to come back and see me again. And I want to make sure that the attack you had is not repeated.

And so I was at Bellevue for six days. I got out the following Saturday afternoon and it was one o'clock. I walked out: steamy, hazy, New York summer day, and I had an epiphany experience like Paul on the road to Damascus. Scales falling from eyes, and everything before in my life became BC and from that moment on became AD. And I just remember, for instance, looking at a guy who was selling sabret hot dogs on the corner of 26th and 1st and thinking, what an incredible creator to have included this facet of culture into life. And I entered this bliss state that lasted nine or 10 days.

But after about a week, it began to fade. And I was like the protagonist in the short story “Flowers for Algernon”, where I felt like I'd been experiencing temporarily a genius status, but slowly I was coming back to normal life. And I didn't want that to happen. I thought, I've had the most profound week of my life for a sense of insight, sense of connection with all the world, a sense of overwhelming gratitude. And I did not want to go back to a sleepwalking existence. So I thought, number one, I'm acknowledging an undeniable for me - and it has not changed in all these years since 1987 - sense of God. However, I did not have a specific religion to return to.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

You were not raised in any particular tradition or nominally something.

SCOTT CARTER:

We were Protestants. But we were the sort of Protestants that whenever we would move to a new neighborhood, we were looked for something within a 10 minute or 15 minute radius where the people were nice. And for my parents, the coffee and donuts served after the service were equal sacraments to wafer and wine at the ceremony.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

I think that's actually one of the tenets of most Protestant churches. And not the worst thing.

SCOTT CARTER:

We were Lutherans. We were Methodists. We were Presbyterians, Episcopalians. So I had nothing to return to. So then I just made an agreement with the universe that for the next couple of years, at least if anybody wants to talk to me about religion, I can't be sarcastic. I can't walk away. I've to stop and just listen. And if anybody wants me to read any material, any kind of literature, I will have to read it. And if anybody wants me to attend any kind of ceremony, I will have to go. And so I do.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Wow that is a wild… That is a very strong commitment. There's something so beautiful about that, that open heart, that intentional curiosity which is, I think, at the foundation of all spirituality is like this intentional curiosity that says, I'm open to where this might lead. But that's a discipline, because we are busy people who often, we're looking for a reason to write someone off or something off. And so that's an incredible opening to… And that's a long time ago.

SCOTT CARTER:

It's a long time ago, and I was just, I spent last week at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, where there was a new play festival and this new play that I've been writing was done there. And one of the questions in the playwrights panel was, what do you want audiences to take away from this? And so I gave a very brief encapsulation of what I just told you, but I ended by saying, I think everything I've done since 1987 has been with one goal in mind, which is to tell people to wake up.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

There's something that actually kind of transcends all - or it connects all religious traditions in that. It makes me think of a Buddhist sense of seeing through clearly. But also, it's become, somehow, a negative word, but being “woke” in the Black Christian tradition was really being awake to what was happening around you. And there was a spiritual element to it.

So being awake, it just allows you to interact with the world, and I think that that is so exciting. And you have used art, which I actually think is one of the most profound ways to interact with spirituality and religion. For me, before I went to seminary, I had a record company. I've always thought, the way I've understood, the way I've been communicated with about spirituality and songs that touched me, whether it's David Bowie singing about somebody up there likes me. All these songs that – some people may not be listening with that sensibility like you are. But when you are listening to that and are awake to that, the world becomes very exciting.

Another New York story. I remember when I was in seminary and I was really kind of thinking about, what am I supposed to do? And all of a sudden I had one of those moments. I was in a subway car and I just looked around and I said, oh my God, look at all this beauty - which is not always the way we appreciate a subway car. But if you can see it in that moment, and every one of them is living these rich, vivid lives that I don't yet know about, but if you can see the world in that way, it does change everything and so it's really exciting.

SCOTT CARTER:

Well Paul, you're sparking me toward many different associations, but the one that you just mentioned now about the subway car and beauty. Think about the movie American Beauty written by Alan Ball, who's a friend of mine. And the notion in the middle of the film is about watching a paper bag be blown around in the air.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Oh my God, I remember crying when I saw that… I was in seminary when that film came out, and that sequence, I was like, oh my God, that's it. You know what I mean? People don't know. Set it up just so – I want to talk about everything else you've done but this is so beautiful, this one scene in American Beauty.

SCOTT CARTER:

I'm probably going to get it wrong, but there is a scene where someone describes to someone else in the movie - and while that happens, there is a flashback, a silent flashback. The character describes a moment in New York… Is it in New York? It's in a city setting, but I think maybe it's suburban, but watching a gust of wind in an urban setting and watching a trash bag be kind of tossed around and seeing this not as something trivial or insignificant, but seeing…

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Or even as trash!

SCOTT CARTER:

Or even as trash, it's more seeing something beautiful is occurring. And it's one of those images that, as you listen to the voiceover describing what this moment meant to the character and watching this little trash bag be tossed around, almost like Dorothy's house at the beginning of Wizard of Oz, as it moves up into the cyclone and is eventually going to go off into this fantasy kingdom, you can start projecting things into that: that we're all tossed around, that we're on a planet that is orbiting at every moment, though we think we're still and we're standing or sitting in one place. We're actually hurtling through the solar system at this moment, like the trash.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

And that you can see beauty all around us. All around us. Listen, I could riff on all of this for hours with you. But you have all of this, all of this, walking around awake and looking for it to be awake, and then you go work in television. And you worked, again, on many, many different shows, but famously on Bill Maher. There's a snarkiness, in some ways, to that show. I mean, there's a curiosity, but I'm just wondering, how was it working in that? It's not a gentle field, television. It's a very intense sort of like – first of all, competitive. But then, also, you have to keep winning in a way or you get cut. And I'm curious how you maintained… And we will get to Ye Gods, but I am just like, coming along, having this epiphany and awakening and then going into the beautiful field of television. Which, there so many talented people and so much beauty in television, and it's changed my life in so many ways. It's all of ours. But at the same time, the industry of it, my sense is it can be quite brutal - and you were on a show that kind of kept being very hard hitting. Tell me about how you kept this going as you were doing television?

SCOTT CARTER:

Well, first of all, let me say that I don't think I've always kept everything going. I have had periods where I've gotten absorbed by the daily pressures that you are accurately describing, and then have had to figure out ways, like meditation, like attending ceremonies, like keeping contact with friends of mine who keep me grounded. It's a little bit like when my bliss state in 1987 began to fade, and it's almost like I needed, for my life, I needed like a crowbar in a window to keep the window propped up - because if I didn't have that crowbar propping the window open, the window would gradually shut.

So one of the ways that I gave myself, a way of keeping connected to this bliss state, was… Well, one of the things that you're told and I learned this over a period of time is, don't try to keep it. That a lot of sacred teachings teach that it's almost like a season that visits you but it's not going to be there forever. And the way to sort of - maybe “ruin” is too strong of a word, but the way to lose it quickest is to try to be holding on to it, and to not be honest about some of the less pleasant thoughts that are flowing through you that you need to acknowledge and you need to deal with, because they're bringing up to you things in your character, things that you have harbored or were indoctrinated from childhood or whatever. But there are things about your own character that you need to examine and resolve if you're going to get to a sustained foundation of peace.

One of the things I did was, when I got out of the hospital in June of ‘87, I had scheduled on September 2nd that year, there was a little club called Who's on First on 1st and 64th Street. And they had a tiny comedy club in the basement, maybe sat 40, 45 people - and I had scheduled, as many of the regular performers there did, an evening of doing character sketches. And when I got out of the hospital, after the bliss state began to fade, I said to myself, you know what, I've got about 6 weeks, I've got a little less than 2 months to do something. I'm going to write a new show. I'm going to do a full-length monologue that is going to describe this experience that I just went through. And this way I will have the words forever for myself, and I will always be able to look back at them and they will get me back to this time.

Now, In in my earlier and in their earlier incarnation, when I lived in LA for a couple of years before I returned to New York, and for a while during the Boogie Nights era, I had worked in a pornography factory writing pornography while I was beginning to become a standup. So what I wanted to do for my monologue was, I wanted to - because I've always resisted when somebody came at me talking to me about God, I would immediately dismiss them. The word God was a turn off. Any kind of affiliation with organized religion was off-putting to me. So I thought, if I'm going to do a show, I want to start going into the the most sordid aspects of myself and lower myself in the audience's eye - also with a lot of humor.

So what I did was, I did the first act - it was a full-length evening with an intermission - the first act was about writing pornography. How did I come to be this guy doing this? And then the second half began with the asthma attack, and then described what I went through for the first month or so - because things were still changing in me as I was writing this monologue.

There's a very funny comedian who's been an actor on Mad Men and also Billions named Alan Havy, who was a good friend of mine at the time. And I told him I'm preparing this monologue, and first act’s going to be about pornography; second act’s going to be about a religious epiphany. He goes, “Use the title ‘Heavy Breathing’.” So he gave me that title that united the first half with the second half.

And the second night that I performed it - I think I performed it three nights - the first night that I performed it, two people came to show up: Alan was one, and another was a comedian named Steve Sgrovan. And they came, and within a couple of months, both Steve and then later Alan were offered television shows as hosts where they got to hire writers. And Steve hired me, and then Alan hired me, and then I became the producer of Alan’s show which was the beginning of what became Comedy Central. And that led me to Politically Incorrect.

So to answer - this is a very long answer to your very adroit question about how to deal in television - I've always thought: that's what I'm adding. What I am adding to this project Is a sense of compassion. My goal is, on a team, to be treating everyone with respect and love. To be treating every guest that comes on with love. To be treating the hosts, everybody I'm working with. That's my goal. I don't always achieve it, but that's my goal. And so in the case of Politically Incorrect, I was able to establish a rapport with conservatives who were booked, who thought that they were being booked to be mocked. And very often these people became friends of mine.

I would explain to them the ground rules, and then Bill did a really smart thing early on, which was, he got a blue five-by-eight card and he drew a line down the middle of it. And on the left side, he wrote every liberal idea that he believes in. But on the right side, he wrote down every conservative idea that he believes in. And during the commercial breaks, he would often share with a conservative guest, look, here are my beliefs. Here are my political or cultural beliefs - and the conservatives would be surprised that he sometimes saw things from their point of view.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Huh. Well, thinking through all of that, what I love - first of all, the thing about the epiphany fading, as you say, that's a classic idea. We have mountaintop experiences, and then we are often in the valley. And figuring out how to traverse the valley, and not assume that every goal is to get to the mountaintop. Some things happen on the mountaintop. Most of it happens in the valley. And you know, I'm of a certain age; when I'm talking to younger religious folks now and I'm like, I've had moments of clarity less than - I'm holding up five fingers. I don't live in that clarity moment. I live in the moment of trying to find truth and trying to do the best I can.

But I also want to say, part of what you're talking about is a discipline, and I think the reason people do go to church and the reason that people go to mosque or go to meditation center or go to – is actually to just say, okay, I'm going to commit this amount of time. Maybe nothing will happen. But let me give it a shot. I do think that that's worth mentioning for people who just write off people who do attend services. I have two young kids, now, and we haven't been perfect about taking them. But when we take them, there's nothing else in their week that is like going to this Episcopal service that we have, where people are saying things that they don't hear in other places.

The other thing I'll say about your story and your show, that's like a classic witness testimony. You could do that in any church. You were like, you know, that happened to you. You had this life, and then you have the next life. And by the way, I had a big life like that. Not that I was writing for pornography, but I had a record company, doing drugs, all that stuff. Then I did have a time where I took a different turn. I actually am not embarrassed about what I did. I don't regret it. It made me who I am, fully. I also don't think we have to shame people for where they are and what they're doing. I'll just say that for the record.

SCOTT CARTER:

I completely agree with that. And I think that, well, the Bible is full of examples of people who have questionable action early in life, and then something calls them to a higher mode of being.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

I agree. I mean that's exactly it. Anyway, we cannot get through this entire podcast without talking about Ye Gods, okay? So I'm going to force you to talk about it. But I really appreciate that you really did answer all these questions. Like how do you move through life with this epiphany? And by the way, I know you're encapsulating this in a few words, and all of it takes work. All of it is experience. Most of it is not glamorous or incredibly wonderful or gratifying. A lot of it is really hard, and so I totally appreciate that. But I do think it's wonderful.

Quick question. Do you know Arianna Huffington?

SCOTT CARTER:

Of course. Arianna Huffington, when I was writing my first new play, while working in television, I started writing a play, did 100 drafts over decades, and finally it started being performed in 2014. Was kept in playhouse here in Los Angeles, it's been all around the country and still keeps being performed. Been in 27 cities, four countries.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

What's the name of the play?

SCOTT CARTER:

What's the name of the play? The Gospel According to Thomas Jefferson, Charles Dickens and Count Leo Tolstoy. And then there's a colon and the word then is: Discord. And people refer to the play as Discord. But these three people all wrote their own version of the Gospel.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Yes, yes, they did.

SCOTT CARTER:

I think that I am the first person in recorded history to realize that all three did this, and then I spent decades researching and writing to get them all in a liminal setting where each of the three thinks that his path to salvation depends on convincing the other two that their theology is incorrect.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Oh, that’s good. That’s good.

SCOTT CARTER:

Anyway, Arianna had, when she used to live in LA, she had this big mansion in Brentwood and she did, at Christmas time, with a, maybe, I don't know, it seemed like a 20-foot-high Christmas tree, she had me do an early reading of this play. And one of the people who came to see it - there were a lot of… I remember Tim Robbins or Jay Cutler, but one of them was Shirley MacLaine. And afterwards Shirley MacLaine came up to me and said, “We need to have lunch. I need to tell you something.” And I thought, this is why you get into show business - to be asked to lunch with Shirley MacLaine.

So a week or so later, I meet her at this very dark restaurant in Malibu and we get to a table. She orders a bottle of wine, and she begins to tell me about how her friend, Stephen Hawking, is the reincarnation of Sir Isaac Newton. And I need to be adding Newton to my cast. And I said to her, you know, it's taken me 25 years to get all three of these people researched to the point where I can accurately depict both their personalities, viewpoints, and their religion. And if I were to add Isaac Newton now, this play is never going to be finished if I keep adding people. But I tremendously thank you for caring enough to wish to make this suggestion to me.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Yeah. Well, so Arianna, I approached Arianna about starting the religion section of the Huffington Post, which I did. And I did it for seven years. We were the largest religion website in the country, doing that with Arianna. But right when we started, she said, you know what? You should go on Bill Maher. I know a guy. And I think she was talking about you. It never happened. But it triggered something in me. I was like, I think that this might be the guy.

Anyway, we're coming to the end of the show, dude. And the whole idea was, we were going to pitch Ye Gods to my audience. You're listening. Ye Gods is an amazing podcast. First of all, the list of people you have on this show is because you've been in Hollywood for so long. You have amazing people. Listen, what I like about it, you have the celebrities that are incredible and everybody is like, my God, there's Martin Short. I mean, that must be incredible. You also have people I've never heard of, frankly. But all of them have something that sparks in you a desire to talk to them. So why don't you talk about, what do you hope for when you have someone come on? What is your goal when you have a conversation, either with someone who's in the pantheon of celebrities in America, or someone who fascinates you. I assume you approach them similarly.

SCOTT CARTER:

Yes, I try to approach everybody in the same way. And what I say is what we're going to talk about - it could be religion, it could be faith - but what the underlying foundation here is, I want to find out from you the rules by which you judge your own behavior and the behavior of other people to be appropriate or inappropriate.

So, for example, you mentioned Martin Short, who was the first guest when we relaunched Ye Gods on the NPR network. He was raised Catholic in Canada. When he was 12 years old, his 24-year-old oldest brother was killed in a traffic accident, in a car accident. He fell asleep at the wheel. And members of the church told 12-year-old Marty that God works in mysterious ways, which seemed an affront to him. He rebelled against it.

And he also dismissed, early in his career, when he started to become famous, people would say, “Oh, you became a comic because you had so much tragedy early on.” His brother died when he was 12; both of his parents died before he was 20. And he maintains the opposite: that I grew up in such a loving laughing creative family that that has allowed me to withstand tragedies in my life.

But what's interesting in the podcast episode with him is he has, for over 40 years now, every Monday, he does the same thing, which is he goes through what he calls the nine categories and evaluates how he's doing in them in his life. The first thing he does is he weighs himself. And for decades, he wanted to be 142 pounds. Now he's 75 and he gives himself to 148. He goes through nine categories.

And this came up when he first got out of college, he was cast in the Toronto production of Godspell. And the other people of Godspell were, the woman who became his girlfriend, Gilda Radner. Gene Levy, Dave Thomas, Christ was played by Victor Garber. The musical director was Paul Schaeffer. It ran for over 500 performances. So he thought, early on, I'm going to have this blessed career in show business where I will always work.

Well, when the show closed, he had trouble getting work. So that's how he developed this notion of the nine categories, and every Monday he goes through this. Now he does it on a computer. He used to do it in notebooks, but he evaluates – so, for instance, how is he doing with his family? The family that he has created. How is he doing with the family that he was born into? How is he doing with friends? How is he doing with health? Because he said, I realized what I was doing was putting too many eggs in the career basket. And when I got depressed by, after a year and a half of working and everybody loving everything I did and having a blast every night, eight times a week, I was alone and I was auditioning and I wasn't getting the auditions, and I realized I was putting too many eggs in the career basket. And maybe what I should try and do is be a better friend. Maybe what I should try and do is be a better father or a better husband or a better…

He also talks about health. Maybe I should be eating better. Maybe I should be exercising more. I forget all the nine categories. You can hear them if you listen to the episode, but this has become, in the same way that I meditate every day, he does this once a week - and it has grounded him and allowed him to withstand ups and downs in a long, long career. And also to be a wonderful … I would say there's not a better friend to have in this life than Martin Short.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

He certainly comes across that way. He's someone who I've never met, but certainly, he has a magnetic personality. I always stop my scrolling when he's on my screen. I'm like, I want to hear what he has to say.

I think one of the things I love about Ye Gods is that you really do have this wide cast.I remember when I was at Huffington Post, I would interview like Jimmy Carter one day and then RuPaul the next day. Everyone has something to say and everyone is actually really seriously asking the question that you're asking of your people, which is, what is the way you're approaching the world? And spiritual resources are not defined by necessarily religious categories, although that's a really important element of it. People are forging paths and that's what you did.

Before we get to the end of the show, we're living in a particular context and so none of our spirituality or none of these practices are done just for us, personally, or out of context. We have a context in America that I think about a lot because of my work, which anyone listening to this show understands that I'm very concerned about the attack on the pluralistic nature of our country. How do the questions that you're asking of these individuals around their private well-being and practice translate into how they interact with this cultural moment that we're in? We don't have to restrict you to that. But any cultural wider context of of really difficult challenges happening, especially to marginalized communities, but really to our country, to our democracy. What are ways that you think about making that connection or inviting that thought? Or maybe I'm putting too many words or too many ideas out there for you…

SCOTT CARTER:

No, I'm happy to answer this. Number one, I would say that these days when people, if I talk to somebody, somebody calls me up and I haven't talked to them for a while or I run into them on the street and they say, how are you? I always say, I've got to answer in two ways. There's one way, how I am with my career and my health and my family and my friends. And there's another way, with the greater world that's outside of how I individually am. And depending on what day it is, that has greater or less impact on me and how I'm living my life. Number one.

Number two, during World War II, Winston Churchill got on the radio and told the British people, these are not hard times. Now, this is a time when England was being bombed every night by the Nazis. And he said, “These are not hard times. These are great times, the greatest our country has ever known.” What I think is that no matter where you are in the political spectrum, no matter where you are in your life, no matter what your faith or lack of faith, we all share the same existential situation: that we know that this life on earth is temporary, but when it ends, many of us have notions of what's going to happen. Or maybe nothing will happen when we die. But nobody really knows for sure.

There's a quote that I love from Thomas Jefferson, where he says he stopped speculating on the afterlife and decided, instead, to rest his head on a pillow of ignorance which God had made soft for him, knowing how often he should need to use it. And that's how I am. My belief in God has not wavered since 1987, but I have to think that a creator of a universe has resources beyond my imaginative ability to predict. And so I focus on what is happening in this life. How am I to everyone? One of the things at Baylor when I was addressing a group of students in this playwright panel, I said, every interaction in your life is sacred and character is who you are to people who you do not think can help you.

And so I try to live by that. Think about people who suffered the Holocaust. Think about people who suffered. Ken Burns, who's appeared on Ye Gods, he's going to be on for the second time to promote The American Revolution. But think about the challenges of people who, for their entire lives, thought of themselves as English colonists and then got behind the notion that, we're going to declare our independence. Think of how difficult that time period was, how difficult the Civil War - to invoke another Ken Burns project - how difficult that was. How difficult the civil rights struggle has been. But at every moment, if you believe in God, I think you have to believe that there is some referendum for how you think and how you are with everybody that you come in contact with, and that there is a higher jurisdiction that will be adjudicating.

One of the questions that I ask everybody at the end of each episode is, what do you think happens when you die? And do you think that there will be a referendum on how you have lived your life? And I'm intrigued by the panorama of answers that I get to that. But I think that one of the things I keep saying to myself is: why should life be easy? Why should this time on Earth not be challenging every day? And what is happening every day is, you're being challenged to live who you often say you are. You're getting challenged to prove that that is who you are.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Scott Carter is the creator, executive producer and host of the Ye Gods with Scott Carter podcast, distributed by The NPR Network.

Scott, thank you so very much for taking this time for The State of Belief and congratulations on this incredible new venture.

SCOTT CARTER:

Thank you so much, Paul. It has been a delight. And thank you for the work that you've been doing. I feel like yours and only a couple of other projects are antecedents to what I feel like I'm trying to do, or I feel it's like what I'm compelled to do.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Thank you so much.

Jewish-Muslim Solidarity: Moral Witness in Pressing Times

Highlights from a Capitol Hill briefing on Jewish-Muslim solidarity as a defense against authoritarianism, featuring prominent Muslim and Jewish leaders and lawmakers. With discussion and inspiration from host Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush and interfaith organizer Maggie Siddiqi.

We The People v Trump with Democracy Forward's Skye Perryman

Host Paul Brandeis Raushenbush talks with Democracy Forward President and CEO Skye Perryman about the first year of the second Trump administration. Skye describes how, amid a flood of policies and orders emanating from the White House, Democracy Forward's attorneys have brought many hundreds of challenges in court - and have prevailed in a great majority of them.